Providing social housing with deep retrofits — enough to protect people from climate change and earthquakes, while reducing energy consumption and carbon pollution — costs about 60 per cent more than routine upgrades, but falls far short of the cost of a new building, a new B.C.-focused report has found.

Published by the Pembina Institute Thursday, the brought together 70 professionals, including architects and engineers, and matched them up with construction managers and building owners from across the City of 91原创, the BC Non-Profit Housing Association, Metro 91原创 Housing Corporation and BC Housing.

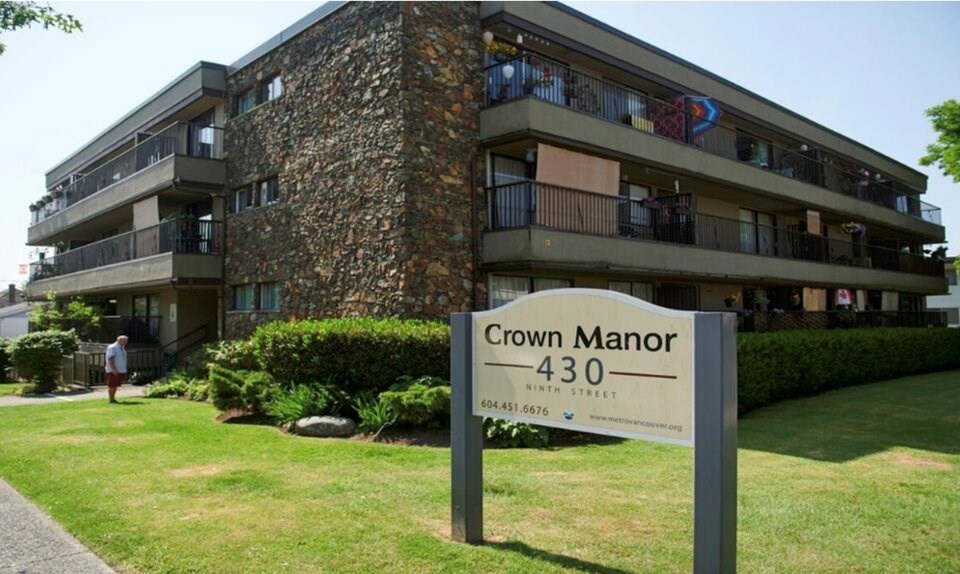

From December 2021 to June 2022, the group worked to understand what it would take to retrofit six low-rise multi-unit residential buildings across Victoria, 91原创, the City of North 91原创, New Westminster, Coquitlam and Kamloops.

Some of the buildings are home to low-income households; others are set up for seniors and people living with disabilities, or people with mental health problems and substance abuse. All represent the kind of social housing units most in need of help.

Betsy Agar, Pembina's program director for buildings and the report's lead author, said the latest work provides real world examples of how deep retrofits could help some of the most vulnerable 91原创s living in “missing middle housing.”

“These buildings are the most affordable to rent and most dire need… They’re just grossly underfunded assets,” Agar said. “We think that this is a once-in-a-generation opportunity.”

“A lot of these major upgrades need to be done, and we could be doing these in a way that also fights climate change and improves the actual living conditions.”

The report comes only weeks after national modelling from the Pembina Institute showed 91原创s living in low-income households will need $42 billion in government and public utility spending over the next 25 years to help retrofit their homes and — defined as those who spent more than double the average on energy bills.

Buildings have uncomfortable temperatures and high energy needs

Together, the teams aimed to design retrofit plans for all six buildings so they can withstand threats from earthquakes and climate change — including wildfire smoke, and extreme heat and cold — while producing drastically less carbon pollution and saving residents money on their energy bills.

Agar said that’s a significant departure from when she got started in the housing industry 30 years ago, when heat pumps weren’t an option and retrofits often meant upgrading a building’s insulation, caulking air leaks or replacing windows in a “piecemeal” way. By contrast, she said “deep retrofits” start with the premise of a long-term plan that takes into account all the threats to a building and opportunities to make residents’ lives better.

Part of the reason the Pembina report targeted the six buildings was because their energy intensity use was 50 per cent higher than the average of similar-sized buildings in B.C. Air leakage was found to be relatively high in all the buildings, while ventilation was relatively poor — with most largely dependent on bathroom and kitchen fans.

In surveys, tenants at Manor House in North 91原创 and Medewiwin in Victoria reported they were least satisfied with summer temperatures and lack of control over temperature. The North Shore residents raised concerns about air flow, while many of the Victoria tenants said they use plug-in heaters to stay warm in the winter.

Agar and her colleagues started their work six months after a record-breaking heat wave scorched western North America, raising indoor temperatures across B.C. and ultimately killing at least 619 people in the province. While tragic, she said the extreme heat event helped build public awareness around a lack of safety in indoor spaces.

“If we had started putting air conditioning in Metro 91原创 buildings before those deep heat waves, I think people probably wouldn’t have been listening,” Agar said. “Even COVID changed things. I’d never really heard people talk about ventilation in buildings the way that people talk about ventilation now.”

“We need to be thinking about, what are the local risks?” Agar added. “It's not just overheating. It’s not just power outages in the winter… Calgary gets a lot of hail. Tornadoes can rip through Ontario.”

Deep retrofit plans drop energy use by at least 44%

When the team of 70 experts looked at the six social housing buildings across B.C., designs for basic upgrades included insulating the roofs or walls in the Kamloops, Victoria, New Westminster and 91原创 buildings. Both the 91原创 and North 91原创 buildings needed air sealing, and both were flagged alongside the Coquitlam building for space heating upgrades.

The plan for deeper retrofits, meanwhile, went much further. They required insulation and air sealing for all six buildings, plus replacing all single-pane windows with double or triple-paned alternatives. In all cases, designs required swapping gas heating units for electric heat pumps, though in the cases of the Kamloops, North 91原创 and New Westminster buildings, they found “significant GHG emissions reductions could also be achieved through a diversified natural gas pathway.”

“This approach helps avoid potential challenges such as the need for electrical panel capacity upgrades,” the report says.

The report projected cost savings if certain buildings installed solar panels, reflective roof coatings, and systems that recovered heat from drain water.

Baseline retrofits were expected to see an average energy savings of 17 per cent. But under the deep retrofit plans, all designs projected a reduction in energy use of between 44 and 90 per cent. Greenhouse gas emissions, meanwhile, were lowered by 68 per cent or more in each of the buildings, the report said.

Deep retrofit costs only make sense under 'alternative business case'

Under standard accounting practices, none of the deep retrofits plans presented in the report paid for themselves over time — something Agar acknowledged is “a big challenge.”

The report found the median cost of a baseline retrofit was $63,000, whereas the cost to build a new unit in a new building ranges between $550,000 to $600,000.

A best-in-class deep retrofit, on the other hand, would likely cost $138,000 per housing unit. That’s below the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s grant limit for retrofit funding, but still about 60 per cent more than baseline retrofits.

Agar warned tearing down buildings to build anew leads to a lot of intangible costs that are hard to quantify — from the costs of re-locating people, to increased medical or mental health problems.

Sticking with basic upgrades could also lead to a number of extra costs, including ongoing mould problems that balloon into expensive medical bills ultimately paid for by taxpayers, or extreme weather events that turn a safe building into a dangerous place.

Once those future costs are added up, Agar says the gap between baseline upgrades and deep retrofits starts to close rapidly. And that doesn’t even begin to consider the cost of carbon released by old buildings.

One estimate from the Global Commission for Adaptation says that every $1 spent on climate adaptation yields $4 in avoided recovery costs. The Insurance Bureau of Canada forecasts identical insurance cost savings when it comes to seismic upgrades.

Agar says those uncounted costs call for “an alternative business case” for social housing.

“We need to find the sweet spot of costs,” she said. “We should be thinking seriously about where public money is better spent.”

Correction: A previous version of this story described Betsy Agar's title as program manager of the Pembina Institute's buildings program. Agar's title is, in fact, the program director.