Inside the basement of The Belmanor, a gas furnace sparks to life with a whoosh. The aging appliance feeds hot water through a network of copper pipes to baseboards across the building’s 14 units.

Upstairs, resident Rebecca Holt fiddles with a knob on one of those old radiators.

“This one is always on,” Holt said. “We have to keep the windows open.”

Built in 91ԭ��’s West End in 1949, the three-storey walk-up still shows signs of old heating technologies phased out in the years after the Second World War. Streaks of black line a trap door where coal was once unloaded into the basement. For decades, oil heated the building. The latest gas furnace was installed in 1995 and is well past its service life.

Gas furnaces like this account for more than half of . It's a pattern that plays out in many of British Columbia's cities and one the province looks to stamp out by reducing emissions from buildings up to 64 per cent below 2007 levels by 2030. In the past three years, however, the trend has gone the other way, with emissions from residential buildings climbing eight per cent.

How residents of The Belmanor decide to heat their homes next offers a glimpse into what's to come — thousands of buildings whose collective decisions will help determine the course of British Columbia's emission reduction targets.

The choice as they see it now: buy a cheaper gas furnace and produce carbon pollution for decades to come, or spend more money on heat pumps now in anticipation of a cheaper electric future.

“We're not just talking about those built in 1949. There are thousands of buildings like this that need to transition,” Holt said. “There are so many buildings that are offering the quality of life that we're so desperate to make more of, that already exists in our space. But we have to take care of them and maintain them.”

“We don’t have time to faff around.”

The task of transitioning furnaces to heat pumps requires a vast re-tooling of the private sector. But it also needs money — a point Premier David Eby drew attention to last month when at a press conference he flashed a “I [heart] heat pump” T-shirt in support of a federal incentive plan.

Currently, B.C. homeowners who want to switch from a gas furnace to a heat pump can receive up to $11,000 through run by BC Hydro and the federal and provincial governments. The rebates and the up to a detached home can save in electricity costs have helped drive an explosion of interest in heat pumps.

Between 2013 and 2023, the share of heat pumps in 91ԭ�� homes more than doubled to , according to .

Despite that interest and lofty , many barriers to heat pumps remain.

Industry data shows an 18 per cent increase in heat pumps sales in the four years leading up to 2022. Yet over that same time, 91ԭ��s bought 10 times as many air conditioner units, a gap the 91ԭ�� Climate Institute has partially attributed to a of heat pumps.

One of the biggest problems, say critics, are early retrofit that often only apply to single-family homes, townhouses or towers. That has left thousands of “” multi-family apartment buildings behind, largely in Metro 91ԭ�� and the Capital Regional District.

In 91ԭ�� alone, nearly are in the same class as The Belmanor and account for about 11 per cent of the sector’s total carbon pollution. In Victoria, a post-war building boom led to the construction of 46 per cent of all rental buildings still standing. Of those, “all-gas, low-rise" buildings were found to have the highest intensity of greenhouse gas emissions, according to a 2023 Victoria city staff .

“Every building has to do this,” said Jordan Fisher, a Victoria-based chief decarbonization officer at the building retrofit company Fresco. “It’s really a matter of which are the buildings [that] are going to be torn down, and which are kept.”

The investment required to retrofit Canada's aging buildings is expected to cost governments $15 billion per year over the next two decades, according to a 2021 from the climate think tank the Pembina Institute.

No government has committed to fund such an expansive program. And before that can happen, provinces like B.C. still need to figure out how many aging buildings will require green retrofits, said Tony Gioventu, executive director of the Condominium Home Owners Association of B.C.

“That's another one of our challenges,” said Gioventu. “We don't have a central registry.”

A spokesperson for the Ministry of Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation said it is currently working on an analysis of multi-unit residential buildings across B.C. “to inform future program design.” It's not clear when that work will be finished.

The building gets a green expert

On a recent Friday in December, a group of residents gathered outside The Belmanor's laundry room to chat with this reporter.

“You’re doing the turkey, right?” interjected one older resident on her way out.

Holt nodded.

“Great. I’m doing the mashed potatoes then,” she said with a fist pump.

Sitting on a bench outside The Belmanor's laundry room, Dennis, another longtime resident who declined to provide his last name, said the building has been well maintained by several generations of co-op shareholders. Recently, they came together to re-seal the windows and the building envelope.

Residents of the West End building say its solid foundation and good roof means that with the right energy retrofits, it could last years into the future.

The idea of upgrading the entire building with heat pumps first came up at a board meeting about five years ago. At the time, nobody had the technical expertise to understand the technology nor the experience to navigate the bureaucracy of government programs.

That is until Holt moved in three years later, bringing with her more than two decades of experience developing green public infrastructure — including Canada's , and recreation and aquatic centres across Burnaby, and .

Some residents 'cried when they heard those numbers'

Shortly after her arrival, Holt used her expertise and contacts to figure out what it would take to upgrade the building’s aging heating system. Holt spent hundreds of hours researching, making phone calls and sending emails.

Finally, she was successful in commissioning a $20,000 custom energy study, nearly half of which was covered under the province’s CleanBC program. The goal: find financially sound ways to electrify the building and eliminate the need for natural gas heating, while preventing overheating in the summer.

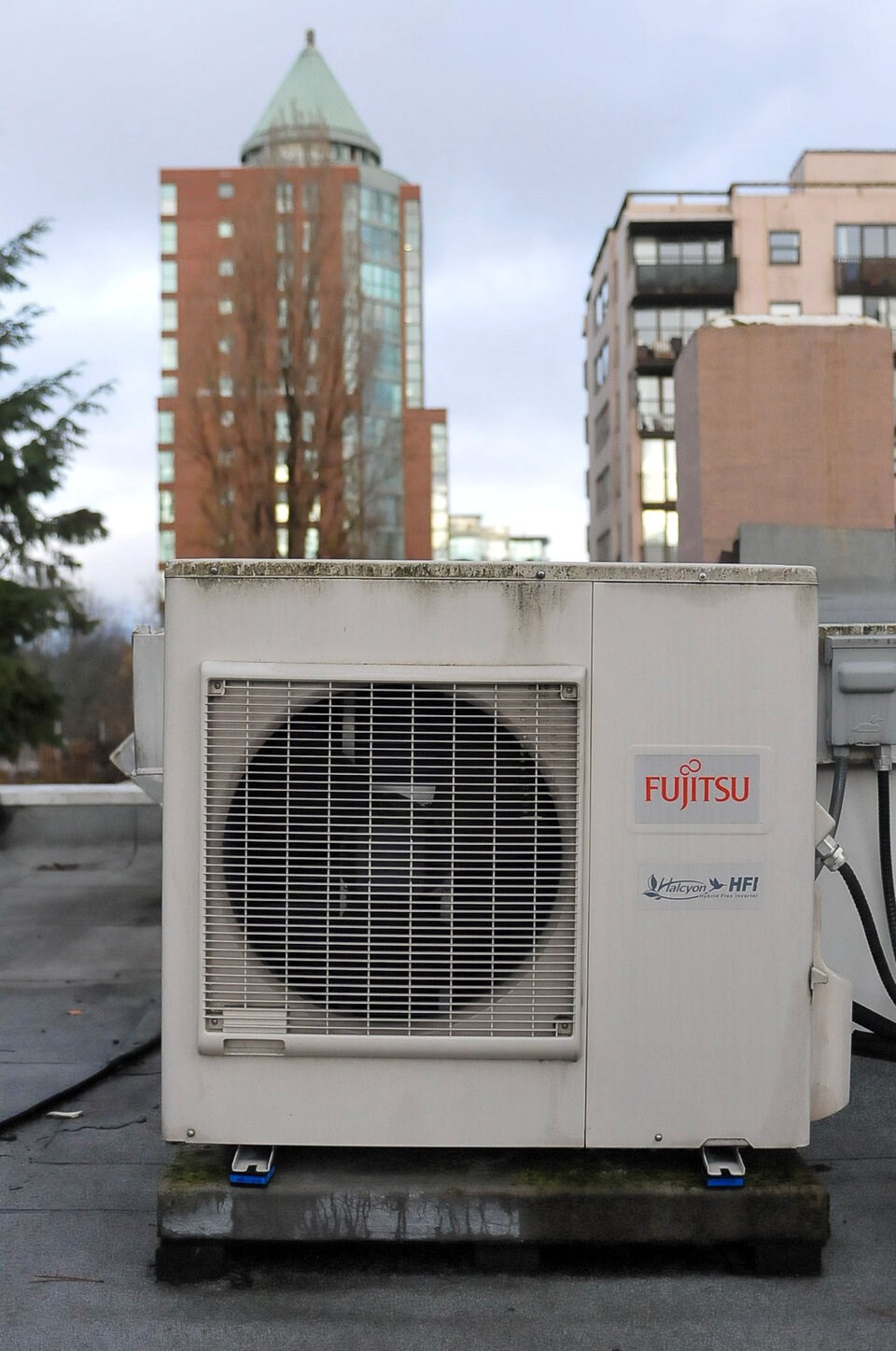

Holt brought the results back to the building’s co-op board earlier this year. The good news was that if the gas boilers were removed, an air source heat pump would eliminate 98 per cent of the building’s emissions — an estimated 70 tonnes in 2022. The new heating and cooling system would also drop operational costs by 42 per cent.

But first, the old building’s electrical services would have to be upgraded. Add the cost of installing two heat pumps — one for heating and cooling and another for hot water — and the report found it would cost the residents over $800,000.

When Holt took those numbers to two contractors, the estimate skyrocketed to roughly $1.2 million. Financing from an energy services company was rejected in August 2023. And a loan from a financial institution would likely come at a prime interest rate, currently a prohibitive 7.2 per cent.

Holt found that every option to decarbonize the building cost far more than the residents could afford.

“Some cried when they heard those numbers,” said Holt. “We’re really at a loss.”

An impossible decision

Mark Winston, a building resident and retired professor who used to run Simon Fraser University’s Centre for Dialogue, stepped in to facilitate the board’s complicated conversations.

At two information meetings this year, Winston said the entire building wanted to go ahead with electrification. Some said the city would eventually evolve so that every building would have to electrify whether they liked it or not. Most said it was the right thing to do in the face of climate change. Everyone cared how their decision would affect their neighbours.

“This building is a real community,” said Winston. “It's a building where neighbours help each other out, where we care for each other, where we take each other to hospitals and we visit each other when we're sick to give each other soup.”

That empathy extends to some residents who live in sun-exposed apartments, described by one owner as “The Inferno.”

“Not having cooling in a building is no longer viable. People suffer in a building like ours,” said Winston. “But at the same time, I can't stomach the idea of throwing my neighbours out, my friends — making them find another place to live, because they live on a Canada Pension Plan and they can't afford to pay the steep price for electrification.”

In a Nov. 16 email to residents, the building's board finally made their recommendation.

At this point, they wrote, “we recommend continuing with natural gas as our energy source for the near future.”

“We hit a wall,” said Winston.

Bureaucracy too complex for non-experts

After the energy study came back, Holt wrote to multiple government ministries, and eventually met with Andrew Pye, a representative with the Ministry of Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation. According to Holt, Pye confirmed a new heat pump incentive program for multi-unit residential buildings will be made available in May 2024.

But the conversation ended with the understanding that the bulk of the expense would still have to be financed by the building’s residents, Holt said.

“It's asking too much of individuals to take on that burden,” said Jessica McIlroy, buildings manager at the Pembina Institute.

McIlroy, who is also a councillor for the City of North 91ԭ��, said The Belmanor's situation is the perfect example of challenges B.C. is facing in its fight to protect missing middle housing.

“A lot of them have been well maintained and are still viable structures,” said McIlroy, ”and we're reaching this point of really critical decisions on replacement.”

“It's kind of a once-in-a-lifetime moment.”

Gioventu of B.C.'s strata association said government funding to help buildings like The Belmanor remains a “big wildcard,” and when it comes to government-backed decarbonization programs, “there isn't really any kind of consistency.”

Many buildings like The Belmanor are expected to require significant electrical system upgrades before heat pumps can be installed. But according to Fisher, the way those costs are paid for often makes burning gas the more attractive option. While FortisBC tends to spread out costs across its client base, BC Hydro still requires individual buildings to cover most of the costs of electrical system upgrades, says Fisher.

That gives the gas utility an advantage, according to the consultant, whose company has worked across B.C. and Alberta with clients spanning small owners and non-profits to governments, developers and utilities.

“The reality is we still have an industry that’s geared toward using fossil fuels for heating and hot water,” Fisher said. “If you’re one of these unlucky buildings, you’re absorbing these massive costs.”

“We have to decide as a society whether we are serious about this or not — not leaving every building on its own trying to figure it out.”

'We need to think strategically'

Minister of Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation Josie Osborne acknowledged retrofitting older buildings “can be an expensive and challenging process.”

“That’s why the province and BC Hydro are currently exploring expanded program options for heat pumps in individual apartments and condo units in multi-unit residential buildings,” she said in an emailed statement.

A spokesperson for the ministry said it is working with the federal government to coordinate heat pump rebates and “simplify the process for people,” but did not give any details on what expanded programs the province is looking at.

“Unfortunately, many older buildings are expensive to upgrade even with public funding available,” said the spokesperson.

Despite its slow start, by 2030, B.C.'s zero carbon building code is expected to drive the fastest transition to electric heating among Canada's four provinces that rely on gas for more than half their heating needs (others include Alberta, Ontario and Saskatchewan), a 2022 from the 91ԭ�� Climate Institute found.

That's little comfort for the residents of a three-storey walk-up in the West End. Until more equitable systems are in place, The Belmanor's experience has shown climate inaction often plays out at a smaller scale — a collection of decisions constrained by a lack of money and nearly impenetrable bureaucracy.

“We need to think strategically,” said Holt. “And right now, nobody is doing that.”