Idealist and pragmatist. Activist and member of the establishment. Workaholic and yoga dad.

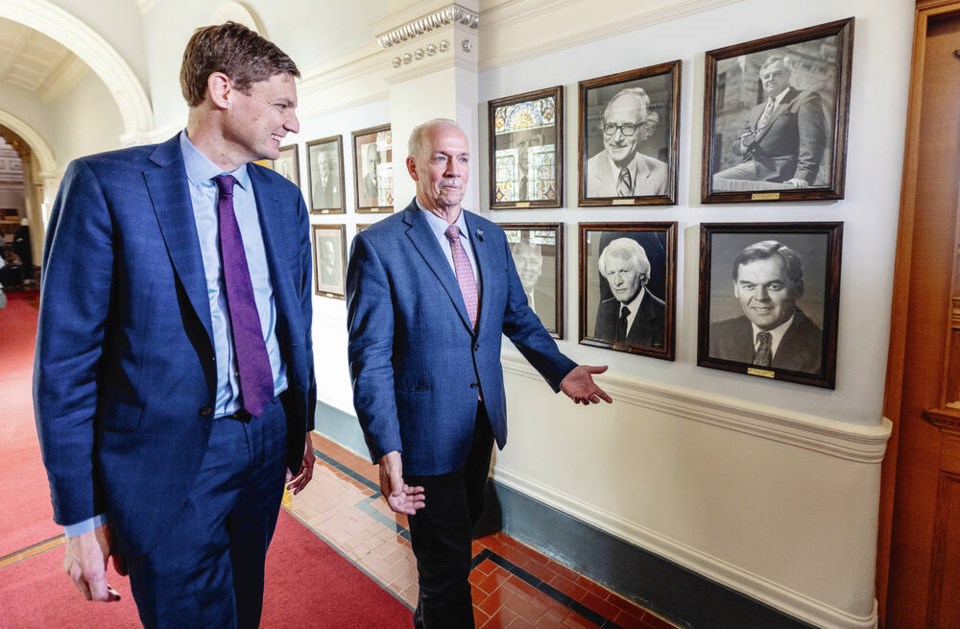

David Eby has been all these things at one point in his career. But as he prepares to be sworn in as B.C.’s 37th premier on Friday — stepping into the shadow of his predecessor John Horgan, one of B.C.’s most popular premiers — perhaps the most important role he must assume is fixer.

Fixer of the root causes of crime, housing unaffordability and a crumbling health care system, intractable issues he’s under pressure to make progress on before he faces B.C. Liberal leader Kevin Falcon in the 2024 election.

Those around him say the 46-year-old father of two is driven, laser-focused and relentless and will likely expect the same from members of his soon-to-be-named cabinet. He’s also not afraid to defy those he believes are standing in the way of progress, which is why he has promised to override local mayors reluctant to approve affordable housing projects.

But his closest confidantes and colleagues say Eby’s first approach is to bring people on side through evidence and impressive research. That’s how, as attorney general, he convinced skeptical cabinet members to embrace his no-fault insurance reforms to end the “dumpster fire” at the Insurance Corp. of B.C., even after the same model proved to be a failure for the NDP government in the 1990s, said Joy MacPhail, the former NDP cabinet minister who was ICBC board chair when the reforms were underway in 2018.

“His approach is calm, methodical, considerate and broad-thinking,” said MacPhail, who remains a mentor to Eby.

As he walked from his downtown Victoria hotel to his transition office behind the legislature building, Eby said he has “very high expectations” of his colleagues, the government and “myself.”

Eby made those expectations clear in a letter to public servants in which he indicated he has little patience for the slow bureaucracy that can stymie change.

The former attorney general and housing minister said he wants to “shrink that distance” between government leadership and front-line civil servants working in hospitals, housing agencies, social services and publicly-funded non-profits, giving those employees more of a voice when it comes to improving the status quo.

Eby has assured the public he’s not planning any radical changes and wants to continue the mandate secured by Horgan after he led the New Democrats to their largest victory in B.C. history in October 2020.

However, his housing platform includes promises to establish a flipping tax to deter real estate speculators, legalize secondary suites in every region and allow developers to replace a single-family home with up to three units in major urban centres.

Eby also signalled an end to fossil-fuel subsidies, an olive branch to environmentalists who supported his opponent Anjali Appadurai, the 32-year-old climate activist who was disqualified from the leadership race in October after an investigation by B.C. NDP’s chief electoral officer found she engaged in improper co-ordination with third-party groups.

Eby will be quick to set the pace and challenge those in his orbit to keep up, said Jeff Ferrier, a public affairs analyst for Hill+Knowlton Strategies and longtime B.C. NDP volunteer who worked in the Ministry of Health from 2021 to 2022.

“I think where Eby’s leadership style is unique is that he’s what I call a pace setter,” Ferrier said. “Where most premiers do a steady jog, Eby is more of an interval runner, alternating periods of steady exercise with short bursts of super-high-intensity work. When it’s time to get things done, you get hands on, you lead from the front, you tell folks around you: ‘Do as I do and follow my lead.’ ”

That’s a good skill to have, Ferrier said, considering Eby is under intense pressure to deal with housing, homelessness, mental health and the acute problem of prolific offenders committing violent attacks in 91Ô´´, Victoria, Kelowna and other urban centres.

The B.C. Liberals have hammered the crime issue in question period, branding Eby the “incoming soft-on-crime premier” as they detail horrific attacks happening regularly.

Eby said he’s already talked to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau about reforms to the Criminal Code bail provisions to give the provinces more powers to deal with repeat offenders.

As for the partisan attacks, Eby said, thanks to his ability growing up to “take flak” from his three younger siblings, he’s got a “long fuse” and isn’t quick to anger.

This is in sharp contrast to Horgan, who in opposition earned the nickname “Angry John” and who, despite softening into the jokey dad as premier, could still let his temper flare during heated debates in the legislature.

Andrew Weaver, former B.C. Green party leader who formed the deal that allowed the NDP to wrest power from the B.C. Liberals in 2017, said while Eby is “thoughtful, articulate and compassionate,” he “has some work to do to become known as the guy for all people like John [Horgan] was.”

Former NDP political strategist Bill Tieleman, who volunteered on the 91Ô´´-Point Grey MLA’s past campaigns, said he’s seen Eby evolve from a fearless civil rights lawyer — who advocated on behalf of marginalized people on the Downtown Eastside with the Pivot Legal Society and who spoke out against police and government overreach as head of the B.C. Civil Liberties Association — to a pragmatic politician who is willing to compromise to get things done.

“I think the problem with people trying to pigeonhole [Eby] is that he is a work in progress,” Tieleman said. “One of the advantages that he’s had of being a workhorse for the government is that he’s actually achieved success in some very difficult files, and in the process changed people’s minds about both the NDP and him. And I mean, that’s how you win elections — change people’s minds.”

Some activists have accused Eby of abandoning his far-left champion-of-the-poor ideals in favour of politically popular sound bites.

The B.C. Civil Liberties Association in August slammed Eby for supporting mandatory treatment for people who repeatedly overdose on illicit drugs, saying he’s “throwing human rights, civil liberties, and evidence under the bus” by advocating for an option he knows will violate people’s Charter rights.

Eby said his ideals haven’t changed but he now advocates for all British Columbians instead of a small segment of people on the Downtown Eastside.

“The big shift I see is that the constituency that I’m advocating for has shifted from one community now to the province,” he said.

“The core of my work has always been to make sure that the systems that are in place in government are actually working for people, that they’re not just propping up a bunch of people who are feeding on the system and breaking the trust of folks that expect government to work for them.”