When Heather Robertson’s son overdosed on toxic drugs last November, he called her from the emergency room in Courtenay.

The Victoria mom was in her car headed up-Island in 10 minutes.

It was the 14th time her 34-year-old son had experienced a heart-stopping overdose in just a year. It’s hard for her to think about.

“I’m not sure that I can really connect to it. It’s almost like that’s too fantastical to even believe in,” she said.

Robertson didn’t know her son was struggling with addiction until April 2020. The following November, he overdosed for the first time.

“At some point early on, I realized that my son might not survive this. There’s actually a really good chance that he won’t survive this. … I will do everything I possibly can to help save my child’s life and spend all of the wonderful happy time I can with him,” she said.

Paramedics responded to more than twice as many overdose calls in Courtenay in 2021 as the year before, in a record-breaking year that saw the provincial total jump by 31 per cent.

Calls in Courtenay totalled 467 last year, up from 206 in 2020. In the five years before 2021, the city saw an average of 156 annual overdose calls.

The provincial total spiked from 27,068 to 35,525 calls last year, or almost 100 people each day.

There were nearly 6,000 calls on the Island, up 32 per cent.

Victoria remains one of the busiest cities for paramedics responding to overdose calls, with 1,952 last year, up 24 per cent from the year previous. The B.C. capital is behind only 91Ô´´ at 9,993 and Surrey with 3,674.

The numbers can seem impersonal to those who haven’t been touched by the toxic drug crisis, until they aren’t.

When B.C. reported a record-breaking 201 drug toxicity deaths last October, the same month a close friend of Robertson’s son died, “my son and I kind of looked at each other and we said: ‘Well, 200 people and Aaron.’ ”

Robertson said she’s glad for those who have not been personally affected by the crisis yet. Through a support group, she said she has met “every kind of person you could imagine” whose kids are struggling with addiction.

“I don’t think anybody is safe from this.”

Del Grimstad, a harm reduction worker at AIDS 91Ô´´ Island in Courtenay, said he thought the number of overdoses in the community was climbing but was surprised calls had more than doubled in the last year.

“It’s just worse and worse drugs on the street and the doctors in this community don’t seem [to want] to let people access safe supply. That’s been very, very limited here. These are all contributing factors, right. The situation just gets more frustrating every day,” he said.

As B.C. continues to break records for overdose calls and deaths, Pender Island-based advocate Leslie McBain said she feels deaths by drug poisoning have become normalized.

“It’s a terrible feeling,” said McBain, who lost her only child, Jordan Miller, to an overdose in 2014 when he was 25 years old. “It’s as though — take any disease — deaths by cancer or by heart disease or by stroke were being ignored. It’s a disorder.”

Like many, McBain’s organization, Moms Stop the Harm, advocates for a safe supply of pharmaceutical substitutes to illicit drugs and decriminalizing possession for personal use.

The province has made efforts to expand access to prescription alternatives since the pandemic began, but advocates say the current model remains too restrictive, with only a small portion of people able to access a safe supply.

In November, B.C. became the first province in the country to request an exemption from Health Canada under the Controlled Substances Act, asking to decriminalize for personal use up to 4.5 grams of illicit drugs, including heroin, fentanyl, powder and crack cocaine and methamphetamine.

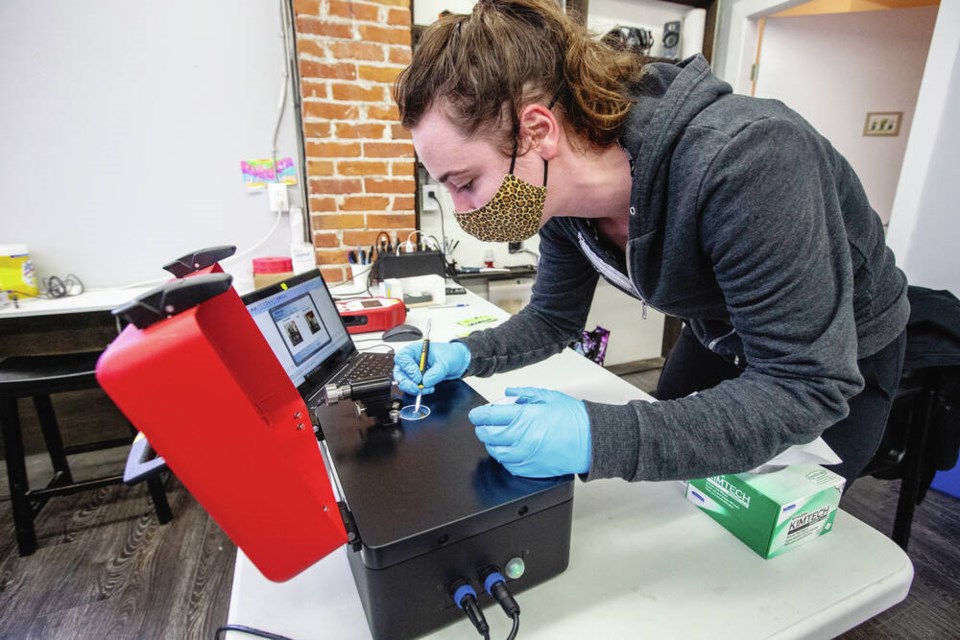

The decriminalization application has allowed the 91Ô´´ Island Drug Checking Project, where anyone can have their substances tested to determine what’s in them, to look at expanding to communities beyond Victoria.

The project, operating out of a Cook Street storefront known as Substance, hopes to open satellite sites in Courtenay, Port Alberni, Campbell River and Duncan by the spring, said Bruce Wallace, a scientist with the 91Ô´´ Institute for Substance Use Research and an associate professor of social work at the University of Victoria who leads the project.

The team spent one day in each of those communities and saw significant interest in people wanting to access drug checking, and a volatile and unpredictable illicit drug supply similar to Victoria’s.

“What we know is that this is not only [an] inner-city health issue, and yet most often, these responses like drug checking are emerging from inner-city settings such as ours. So we really need to increase the scale-up and the reach of drug checking to smaller communities.”

- - -

Comment on this article by sending a letter to the editor: [email protected]