Whatever the cause, when parents lose a child, they lose a connection to a future and their own legacy, say two Island authors and mothers who know.

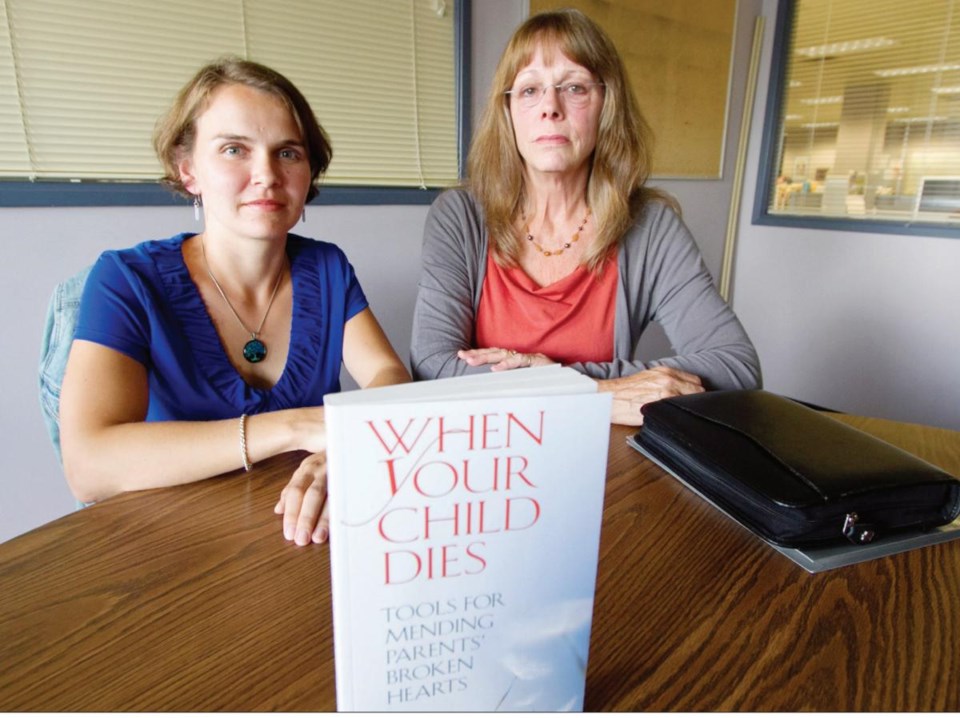

Researcher/writer Avril Nagel of Victoria and therapist/counsellor Randie Clark of Saltspring Island, authors of the soon-to-be-launched book When Your Child Dies, say nobody expects parents to outlive their children.

Instead, we expect children to grow up, leave home and take their own paths. As parents, we assume we will see them grow, have their own children, make us grandparents and carry on after we are gone.

"That's one thing that defines losing a child from any other kind of loss, that loss of future," Nagel said.

Nagel and Clark speak from awful experience. They are both mothers who lost sons - Nagel's died shortly after birth and Clark's was a homicide victim when he was 26.

Both women say the loss is uniquely painful no matter how old the child or the manner of death.

"A child is a child is a child," Clark said. "You are connected to your own child, and that connection stays with you throughout life."

She can still recite the date, Dec. 13, 1995, when her son David was killed in Eugene, Oregon. Two teenage boys decided to finance a motel party with their girlfriends by robbing a hippie - easy, they said later, because a "peacenik" hippie wouldn't fight back.

But her son, accompanied by his seven-months-pregnant wife, would not back down. He was stabbed and died in his wife's arms.

For Clark, now 60, it marked the death of a son she had seen outgrow a troubled, rebellious, punkrocker youth. Mother and son later became the best of friends. More, David was committed and looking forward to life as a husband and father.

So when he died, all of Clark's plans and expectations, of being a witness and part of her son's new life, also died.

"This was my first grandchild, and I was going to watch my son be a daddy," Clark said. "And then he was killed and he never even got to meet his child."

Nagel's loss of her son was also about losing expectations. As long as she can remember, she had always wanted to be a mother.

"There was never a doubt in my mind whether I wanted children or not," Nagel said. "I always knew I wanted a family."

So when her son Alden died shortly after an emergency caesarean section on Oct. 3, 2006, it was like her own self-identity, the one meant to be as a mother, was also lost. Nagel, 30, now with a three-year-old daughter and eight-month-old son, had to work hard to admit she was still meant for motherhood.

"It was a process for me to appreciate that I was still a mother, even though my son didn't survive," Nagel said. "I had to acknowledge that mother part of me that was so hurt was still valid."

Working through their grief, the two authors realized there were few resources to address the special kind of grief felt by parents whose children die.

For example, that grief can involve guilt and near shame. After all, parents should keep their kids safe, right?

"We are supposed to keep our kids close," said Clark, who also has an adult daughter. "That's our job, and when they die, it's like we have failed.

"It doesn't matter how they die, whether they die in a car wreck, from disease, whether they die from homicide or miscarriage, we have failed," she said. "It's a difficult emotion."

There is also a special trauma that seems to be little recognized or understood. It's a genuine emotional injury that requires professional counselling to avoid long-term problems with conditions such as anxiety or depression.

"I had extreme shock for about three months and was walking around in a daze," Nagel said. I didn't realize I was dealing with trauma until I met Randie [Clark]."

The women met during counselling sessions led by Clark.

All in all, the authors say they have been to the place no parent ever wants to think about, and they have used their experience to provide some tools for grieving parents.

"If you tell someone your child has died, they say, 'I can't even imagine,' " Nagel said. "It's true, they can't imagine; nobody can. You can't really describe it until you are actually there.

"But as bereaved parents ourselves, we have created a book that can help other parents."

Nagel and Clark launch their book Sept. 8 from 6 to 8 p.m. at the Moka House, 1633 Hillside Ave.