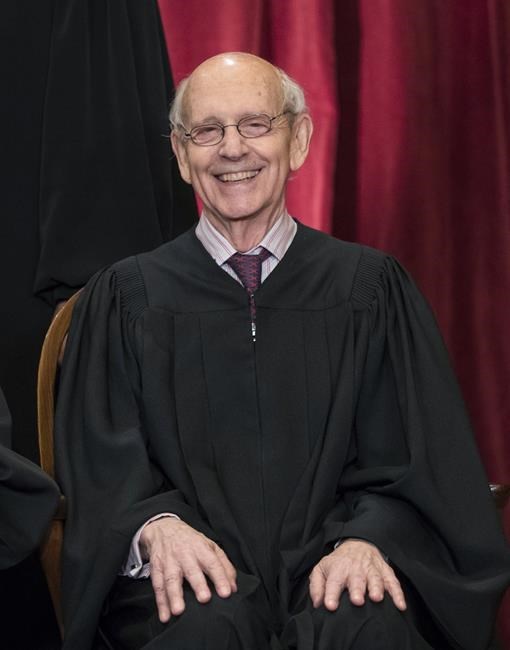

WASHINGTON (AP) — Until last week when he , his successor on the Supreme Court, Justice Stephen Breyer had a rigorous, intellectually challenging job with the . Now the 83-year-old retiree has no briefs to read and no opinions to write.

As a retired justice, Breyer can maintain an office at the Supreme Court if he wants to and also gets a clerk to help him. But like he also gets to chart his own path based on his personality and interests. One example: Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, the , in retirement founded a through computer games.

Here are some things Breyer might do in retirement:

JUDGE

Just because Breyer has retired doesn't mean he has to stop hearing cases. A 1937 law allows retired Supreme Court justices to continue to hear and decide cases on lower federal courts, a practice called “sitting by designation.” A number of retired justices have continued to sit on federal courts of appeal, the level below the Supreme Court, where judges hear cases in three-judge panels.

Justice David Souter, for example, has participated in nearly 500 cases as a judge on the Boston-based federal appeals court since his 2009 retirement from the Supreme Court. Those who know Breyer say they wouldn't be surprised if he joins Souter in not entirely hanging up his robe.

The court Souter sits on, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, would have a particular draw. Breyer was a judge there for 14 years, including four years as the chief judge, before becoming a justice. He was deeply involved in designing the courthouse itself, which was completed in 1998, and he still has a home in Cambridge in addition to one in Washington, D.C.

Breyer has a role as a different kind of judge too. For more than a decade he has been on the jury that awards the prestigious .

TEACH

Before Breyer's title was “judge,” it was “professor.” Breyer, a graduate of Stanford and Harvard law, joined the faculty of his alma mater Harvard in 1967 and taught there for years.

As a professor Breyer was an expert in administrative law, the law surrounding government agencies. Law schools still use a textbook he co-authored. One of his students later became a court colleague. Justice Elena Kagan has called him “my favorite professor.”

It'd be easy for Breyer to return to the classroom if that's what he wanted. A number of the current justices teach law school classes, either during the year or during the summer. International locations are — a way to get out of Washington. France might be an especially attractive location for Breyer, who speaks French. The Supreme Court's press office occasionally distributed copies of .

WRITE

The author of seven books, Breyer has been one of the more prolific Supreme Court authors. Breyer's most recent book, “The Authority of the Court and the Peril of Politics,” was published in 2021. It was a result of a about the power of the court and some of the challenges facing it.

Other retired justices have continued to write and to speak to groups, as Breyer has done frequently while a justice. The late justice John Paul Stevens, who served with Breyer for 16 years, published a memoir a year after leaving the court and followed that with a book detailing six amendments he believed should be made to the Constitution, including clarifying what he believed was a limited Second Amendment right to bear arms. He later .

OTHER PURSUITS

Breyer seemingly has no shortage of other interests to keep him occupied. In 2020, in an interview with The Wall Street Journal about how he was keeping busy during the early days of the coronavirus pandemic he mentioned daily 2-mile runs, meditation, reading nonfiction and French mysteries and family movie nights with his wife, one of his daughters and three of his six grandchildren, who were living with him in Cambridge. He also noted he was sharing cooking duties and detailed a recipe for an Italian pot roast.

In a after Breyer announced his retirement, Chief Justice John Roberts noted Breyer was a “reliable antidote to dead airtime” at lunches the justices share. Topics of interest ran from modern architecture to French cinema, Roberts noted, adding that he also had a “surprisingly comprehensive collection of riddles and knock-knock jokes.”

Jessica Gresko, The Associated Press