TOPEKA, Kan. (AP) — Bob Dole, who overcame disabling war wounds to become a sharp-tongued Senate leader from Kansas, a Republican presidential candidate and then a symbol and celebrant of his dwindling generation of World War II veterans, has died. He was 98.

His wife, Elizabeth Dole, said in an announcement posted on social media that he died early Sunday morning in his sleep.

Dole announced in February 2021 that he’d been diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer. During his 36-year career on Capitol Hill, Dole became one of the most influential legislators and party leaders in the Senate, combining a talent for compromise with a caustic wit, which he often turned on himself but didn’t hesitate to turn on others, too.

He shaped tax policy, foreign policy, farm and nutrition programs and rights for the disabled, enshrining protections against discrimination in employment, education and public services in the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Today’s accessible government offices and national parks, sidewalk ramps and the sign-language interpreters at official local events are just some of the more visible hallmarks of his legacy and that of the fellow lawmakers he rounded up for that sweeping civil rights legislation 30 years ago.

Dole devoted his later years to the cause of wounded veterans, their fallen comrades at Arlington National Cemetery and remembrance of the fading generation of World War II vets.

Thousands of old soldiers massed on the National Mall in 2004 for what Dole, speaking at the dedication of the World War II Memorial there, called “our final reunion.” He’d been a driving force in its creation.

“Our ranks have dwindled,” he said then. “Yet if we gather in the twilight it is brightened by the knowledge that we have kept faith with our comrades.”

Long gone from Kansas, Dole made his life in the capital, at the center of power and then in its shadow upon his retirement, living all the while at the storied Watergate complex. When he left politics and joined a law firm staffed by prominent Democrats, he joked that he brought his dog to work so he would have another Republican to talk to.

He tried three times to become president. The last was in 1996, when he won the Republican nomination only to see President Bill Clinton reelected. He sought his party’s presidential nomination in 1980 and 1988 and was the 1976 GOP vice presidential candidate on the losing ticket with President Gerald Ford.

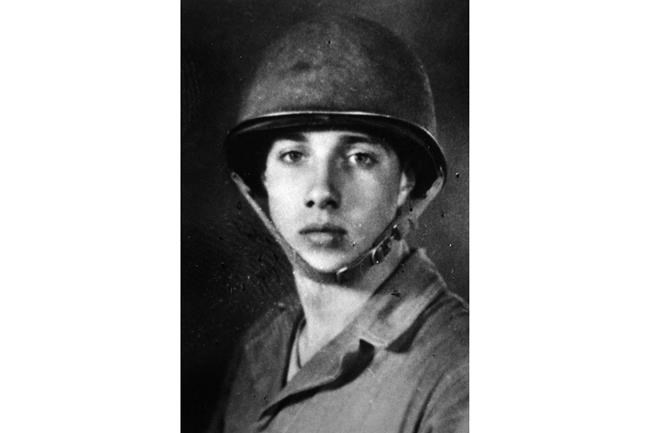

Through all of that he carried the mark of war. Charging a German position in northern Italy in 1945, Dole was hit by a shell fragment that crushed two vertebrae and paralyzed his arms and legs. The young Army platoon leader spent three years recovering in a hospital and never regained use of his right hand.

To avoid embarrassing those trying to shake his right hand, Dole always clutched a pen in it and reached out with his left.

Dole could be merciless with his rivals, whether Democrat or Republican. When George H.W. Bush defeated him in the 1988 New Hampshire Republican primary, Dole snapped: “Stop lying about my record.” If that pales next to the scorching insults in today’s political arena, it was shocking at the time.

But when Bush died in December 2018, old rivalries were forgotten as Dole appeared before Bush’s casket in the Capitol Rotunda. As an aide lifted him from his wheelchair, an ailing and sorrowful Dole slowly steadied himself and saluted his one-time nemesis with his left hand, his chin quivering.

In a vice presidential debate two decades earlier with Walter Mondale, Dole had famously and audaciously branded all of America’s wars that century “Democrat wars.” Mondale shot back that Dole had just “richly earned his reputation as a hatchet man.”

Dole at first denied saying what he had just said on that very public stage, then backed down, and eventually acknowledged he’d gone too far. “I was supposed to go for the jugular,” he said, “and I did — my own.”

For all of his bare-knuckle ways, he was a deep believer in the Senate as an institution and commanded respect and even affection from many Democrats. Just days after Dole announced his dire cancer diagnosis, President Joe Biden visited him at his home to wish him well. The White House said the two were close friends from their days in the Senate.

Biden recalled in a statement Sunday that one of his first meetings outside the White House after being sworn-in as president was with the Doles at their Washington home.

“Like all true friendships, regardless of how much time has passed, we picked up right where we left off, as though it were only yesterday that we were sharing a laugh in the Senate dining room or debating the great issues of the day, often against each other, on the Senate floor,” Biden said. “I saw in his eyes the same light, bravery, and determination I’ve seen so many times before.”

Dole won a seat in Congress in 1960, representing a western Kansas House district. He moved up to the Senate eight years later when Republican incumbent Frank Carlson retired.

There, he antagonized his Senate colleagues with fiercely partisan and sarcastic rhetoric, delivered at the behest of President Richard Nixon. The Kansan was rewarded for his loyalty with the chairmanship of the Republican National Committee in 1971, before Nixon’s presidency collapsed in the Watergate scandal.

He served as a committee chairman, majority leader and minority leader in the Senate during the 1980s and ’90s. Altogether, he was the Republicans’ leader in the Senate for nearly 11 1/2 years, a record until Kentucky Sen. Mitch McConnell broke it in 2018. It was during this period that he earned a reputation as a shrewd, pragmatic legislator, tireless in fashioning compromises.

After Republicans won Senate control, Dole became chairman of the tax-writing Finance Committee and won acclaim from deficit hawks and others for his handling of a 1982 tax bill, in which he persuaded Ronald Reagan’s White House to go along with increasing revenues by $100 billion to ease the federal budget deficit.

“When Bob asked you to do something, that was it. I can tell you so many things we were able to solve by invoking Bob’s name,” said former GOP Sen. Pat Roberts, who served alongside Dole in Kansas' congressional delegation.

But some more conservative Republicans were appalled that Dole had pushed for higher taxes. Georgia Rep. Newt Gingrich branded him “the tax collector for the welfare state.”

Dole became Senate leader in 1985 and served as either majority or minority leader, depending on which party was in charge, until he resigned in 1996 to devote himself to pursuit of the presidency.

That campaign, Dole’s last, was fraught with problems from the start. He ran out of money in the spring, and Democratic ads painted the GOP candidate and the party’s divisive House speaker, Gingrich, with the same brush: as Republicans out to eliminate Medicare. Clinton won by a large margin.

He also faced questions about his age because he was running for president at age 73 — well before Biden was elected weeks before turning 78 in 2020.

Relegated to private life, Dole became an elder statesman who helped Clinton get a chemical-weapons treaty passed. He also tended his wife’s political ambitions. Elizabeth Dole ran unsuccessfully for the Republican presidential nomination in 2000, then served a term as senator from North Carolina.

Dole also endeared himself to the public as the self-deprecating pitchman for the anti-impotence drug Viagra and other products.

He also continued to comment on issues and endorse political candidates.

In 2016, Dole initially backed former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush for the GOP presidential nomination. He later warmed to Donald Trump and eventually endorsed him.

But six weeks after the 2020 election, with Trump still refusing to concede and promoting unfounded claims of voter fraud, Dole told The Kansas City Star, “The election is over.”

He said: “It’s a pretty bitter pill for Trump, but it’s a fact he lost.”

In September 2017, Congress voted to award Dole its highest expression of appreciation for distinguished contributions to the nation, a Congressional Gold Medal. That came a decade after he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Congress honored Dole again in 2019 by promoting him from Army captain to colonel, in recognition of the military service that earned him two Purple Hearts.

Robert Joseph Dole was born July 22, 1923, in Russell, a western Kansas farming and oil community. He was the eldest of four children. His father ran a cream and egg business and managed a grain elevator, and his mother sold sewing machines and vacuum cleaners to help support the family during the Depression. Dole attended the University of Kansas for two years before enlisting in the Army in 1943.

Dole met Phyllis Holden, a therapist at a military hospital, as he was recovering from his war wounds in 1948. They were married and had a daughter, Robin. The couple would divorce in 1972.

Dole began his political career while a student at Washburn University, winning a seat in the Kansas House of Representatives.

He met his second wife, Elizabeth Dole, while she was working for the Nixon White House. She also served on the Federal Trade Commission and as transportation secretary and labor secretary while Dole was in the Senate. They married in 1975.

Dole published a memoir about his wartime experiences and recovery, “One Soldier’s Story,” in 2005. The Dole Institute of Politics on the University of Kansas keeps an archive of World War II veterans from Kansas.

___

Woodward contributed from Washington. Associated Press writers Jennifer C. Kerr and Candace Smith contributed to this report.

___

Online:

National World War II Memorial: http://www.wwiimemorial.com

Video of the WWII memorial is available at: http://customwire.ap.org/dynamic/files/specials/interactives/wwii_memorial/ index.html

John Hanna And Calvin Woodward, The Associated Press