On a recent sunny Friday in Burnaby, Christopher Ogochukwu caught the top rung of a ladder with one hand. He steadied the solar panel teetering on his shoulder, and in one fluid motion, vaulted it toward the roof.

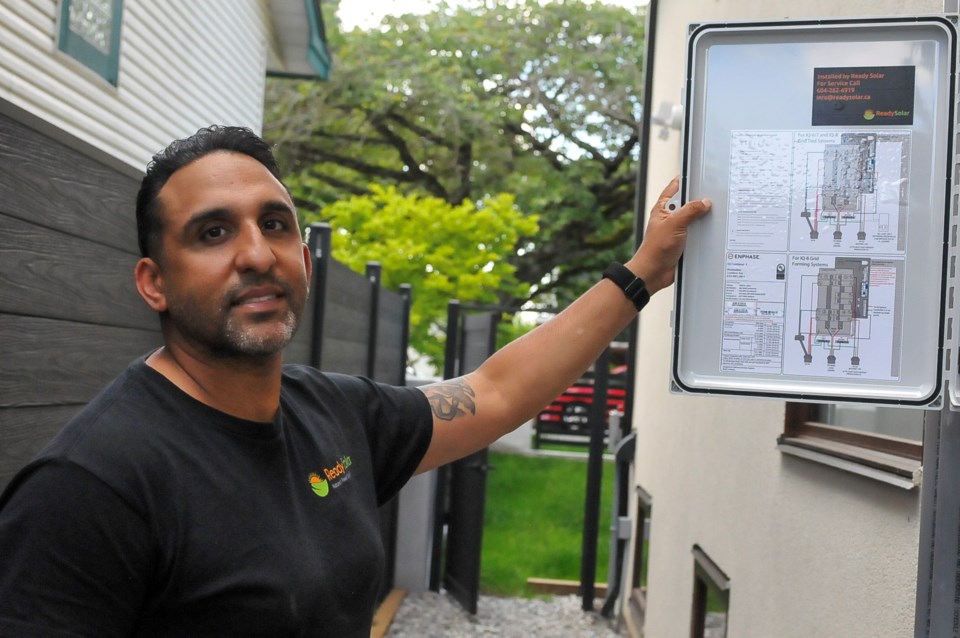

From the ground, Sukhpaul Parmar, head of Ready Solar Inc., looked on as a human chain of electricians and installers angled and bolted down more than two dozen rooftop solar panels, all part of a $40,000 high-end job that would turn the home into its own 10.2-kilowatt power station.

“There’s a lot of misinformation. People think there’s not enough [potential for] solar power in B.C.,” said Parmar. “But there’s population growth, electric vehicles and heat pumps. People have no idea where the power is going to come from.

“It has to come from the sky.”

Parmar’s company is among dozens across the province preparing its workforce for a new wave of interest in solar energy after BC Hydro and the province announced two $5,000 rebates—one for solar panels and another for batteries to store the sun’s energy into the night.

The day after the June 27 announcement, Parmar said he saw a 20-fold increase in calls, a sign the rebates could hail the arrival of a solar boom.

But according to the owners of several B.C. solar companies, those hopes could be short-lived if existing permitting requirements—already leading to months of delays—aren’t streamlined or removed.

“It’s positive. We like to see the government taking action,” said Joe Bowker, operations manager at Victoria-based company Besolar. “But my gut tells me it’s going to be a pain in the ass.”

‘Part of the puzzle’

The push for more rooftop solar comes as BC Hydro forecasts an electricity shortfall of 3,000 gigawatt hours per year by 2028—equivalent to more than half of the generating capacity of the Site C hydroelectric dam or the energy required to power 270,000 homes.

While countries with similarly cloudy winter climates, such as the U.K. and Germany, have turned to solar amid higher energy prices, B.C. has long been backstopped by relatively cheap hydroelectric power. That energy abundance is not expected to last.

Population growth, drought and the simultaneous electrification of industry, housing and transportation are forecast to raise pressures on B.C.’s grid. In response, BC Hydro has put out a call for new power generation, with industrial wind, solar and even tidal electricity projects anticipated to play a bigger role going forward.

BC Hydro spokesperson Saudamini Raina said that at the residential scale, wind and geothermal generation technologies are not as readily available or viable as solar generation.

Raina said the utility would be releasing more details on solar rebate eligibility later this month, but that it would require recipients to sign up as “net metering” customers—households generating their own electricity while hooked up to the grid.

By 2040, BC Hydro aims to have those self-generating solar homes generate 1,000 gigawatt hours of electricity every year. That’s enough to power about 100,000 homes.

BC Hydro says it also plans to expand the solar rebate program to provide up to $150,000 to apartment buildings, schools, small businesses, social housing and Indigenous communities.

Kate Harland, research lead in mitigation at the 91‘≠¥¥ Climate Institute, says rooftop solar panels hooked up to batteries could meaningfully reduce the load at peak hours of electricity consumption, especially in locations where the grid is already under strain.

“This is a part of the puzzle,” Harland said.

For an individual, Harland said solar can lower electricity bills, and batteries can provide a source of backup power should service get knocked out by extreme weather events or an earthquake.

“What they’re trying to do is get people to take control of their own energy,” added Bowker.

B.C. slow off the start

Data suggests that B.C. is starting from a position of weakness. There are currently about 9,500 homes participating in the BC Hydro’s self-generation program, with almost all of them using rooftop solar.

That's at least 50 times less than what’s been achieved per capita in places like the U.K., where a “feed-in tariff” program introduced in 2010 has helped guarantee a return for more than 1.2 million residential solar customers, according to Harland.

B.C. has also regularly fallen in the lower half of provincial and territorial solar energy rankings of benefits to consumers, placing eighth out of 13 in 2023, according to the social enterprise Energy Hub.

There are some bright spots. While in the past, someone on B.C.’s coast may have balked at the idea of putting solar panels on a rooftop that sees scarce sunlight for many months, today’s solar technology undercuts those concerns.

Solar panel-equipped homes in the province’s rainy southwest can easily operate completely off the grid from March to October, while selling energy back to BC Hydro, said several contractors. In the winter months, even cloudy days will generate electricity.

Today, the decision whether to install solar panels tends to hinge more on upfront costs and the time it takes to pay back that initial investment.

In the past, both seemed out of reach.

The average cost to purchase and install a solar panel system in B.C. is around $25,000, according to estimates from three installers. Battery systems vary but can cost an additional $20,000.

The federal government offers an up to $40,000, no-interest, 10-year Canada Greener Homes Loan for eligible retrofits. That, and the new B.C. rebates announced this summer, make the upfront costs a much easier problem to overcome.

Throughout the year, lower utility bills under BC Hydro’s self-generation program are designed to offset repayments on the federal loan, while also locking customers into a contract that protects them against energy inflation, Bowker said.

Solar pay-back periods used to take more than two decades. Today, BC Hydro estimates it takes the average Victoria home 17 years to recoup the initial investment.

There are some caveats. First, a home’s roof must also be in good-enough condition to support solar panels. Federal loan requirements only apply to an applicant’s primary residence, and that home must have a smart meter and receive federal assessments before and after the project is built. The solar power system, meanwhile, must produce at least five kilowatts per hour.

“[The rebates] will certainly drive uptake faster than we’ve seen. But it won’t be for everyone, everywhere. It doesn’t bring the cost down to zero,” warned Harland.

Depending on where a home is built, solar panels also risk damage from wind, wildfires or hail, added Rob de Pruis, the Insurance Bureau of Canada’s national director of consumer and industry relations.

Adding tens of thousands of dollars' worth of solar panels increases the replacement cost of a home and could increase insurance premiums. Anyone looking to install solar panels or a battery system in their home should first call their insurance provider to ensure their home is still covered, said de Pruis.

“You’re changing the risk,” he said. “Do not assume that you have coverage.”

Solar permitting holds B.C. back, say contractors

Over the past 16 years, Tarum Lloyd says he has installed about 600 solar and battery systems across the Caribbean, the U.K. and Canada. Five of those years have been in B.C., where he says demand has gone up and down with the seasons and government financing policies.

“It’s a bit of a solar coaster,” said Lloyd, managing director of 91‘≠¥¥ Solar & Electrical Ltd.

One of the biggest barriers, according to owners of several solar installation companies, is permitting.

Outside a handful of cities, electrical permits fall under the jurisdiction of Technical Safety BC and are approved within days or weeks, several contractors said. But that timeline can also unravel due to requirements from a handful of municipalities and BC Hydro.

Lloyd says jobs in Burnaby, 91‘≠¥¥, Surrey and West 91‘≠¥¥ have taken between four and six months to receive permits. One job in the Township of Langley took nearly a year to get approved, he said.

“In the U.K., I could take a deposit today, and get the job done tomorrow,” said Lloyd. “Here, I have to wait for six months for a permit from the City of 91‘≠¥¥.”

Meanwhile, homes looking to install both solar panels and a battery back-up—a crucial combination that allows solar power to extend into the night—are often required to apply for something known as a “complex (b)” permit through BC Hydro.

“This is a new thing they’ve introduced. It’s a nightmare,” said Lloyd. “I don’t understand why they’re giving themselves so much work if they can’t handle it already.”

“Nowhere else in the world behaves like that in this industry.”

Marcus Downer, one of two owner-operators of OceanVolt Solar & EV on 91‘≠¥¥ Island, said he’s sympathetic that BC Hydro’s net metering department has “a lot on their plate” but current permitting makes pressures from supply chain shortages even worse.

“They complicate it when they don’t need to,” said Downer. “It’s a domino effect.”

Larger solar installation companies like Besolar say they are used to doing the “bureaucratic dance” and have enough cash flow to provide bridge financing for customers waiting for government rebates or loans to come through, said Bowker.

But for many smaller operations, providing financing for months on end is untenable. Lloyd says he’s now contemplating giving it another year or two in 91‘≠¥¥ before moving back to the Caribbean.

In response to questions from Glacier Media, a spokesperson for BC Hydro said the utility was working closely with municipalities on policies and permitting, and that it hopes to “influence processes by creating a Municipal Solar and Battery Permitting Best Practice Guide.”

“We are already engaging municipalities, and the final product will be complete this summer,” said Raina, later adding: “We are not anticipating any delays to starting projects due to the rebate offer.”

Raina did not answer concerns raised by installation companies about “complex (b)” net metering requirements.

Back at the jobsite in Burnaby, the newly installed rooftop solar panels reflected a bright blue sky, a new addition to an old neighbourhood framed by several residential towers.

Workers loaded a van with spools of cables, drills and ladders. Parmar warned that treating solar panel installers “like we’re building houses” was causing a lot of people to go out of business.

Still, the business owner said he remained cautiously excited about the future and had no plans to get out of an industry he sees poised to grow.

“Our advantage is that we’re used to red tape,” said Parmar. “It's stupid but it’s true.”