To address the world’s most challenging problems, you need strong partnerships. With this sentiment in mind, researchers at the University of Victoria (UVic) are collaborating with governments, communities, and different industries to make our world better in remarkable ways—and across countless fields.

UVic is ranked as the world’s number-two university for climate action and for sustaining life on land, and the number-five university for life below water—three key United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—by the Times Higher Education Impact Rankings.

about UVic's commitment to the UN SDGs.

Protecting B.C.’s rockfish

B.C.’s coastal rockfish live long lives, with some, such as the yelloweye rockfish, lasting upwards of 120 years and others living 200 years or more. That makes B.C.’s 37 rockfish species more susceptible to overfishing.

Natalie Ban is one of Canada’s foremost scientists and a UVic professor of environmental studies. She has been working for almost a decade with non-profit and business partners, including Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Galiano Conservancy Association, off Galiano Island. The groups’ public outreach efforts, which now include online resources, are providing lessons to help safeguard a variety of threatened fish species in diverse coastal areas.

"We're showcasing how academia and multiple partners can partner to work together effectively and monitor some of the effects of those outreach programs,” Ban says.

Rock-solid CO2 solution

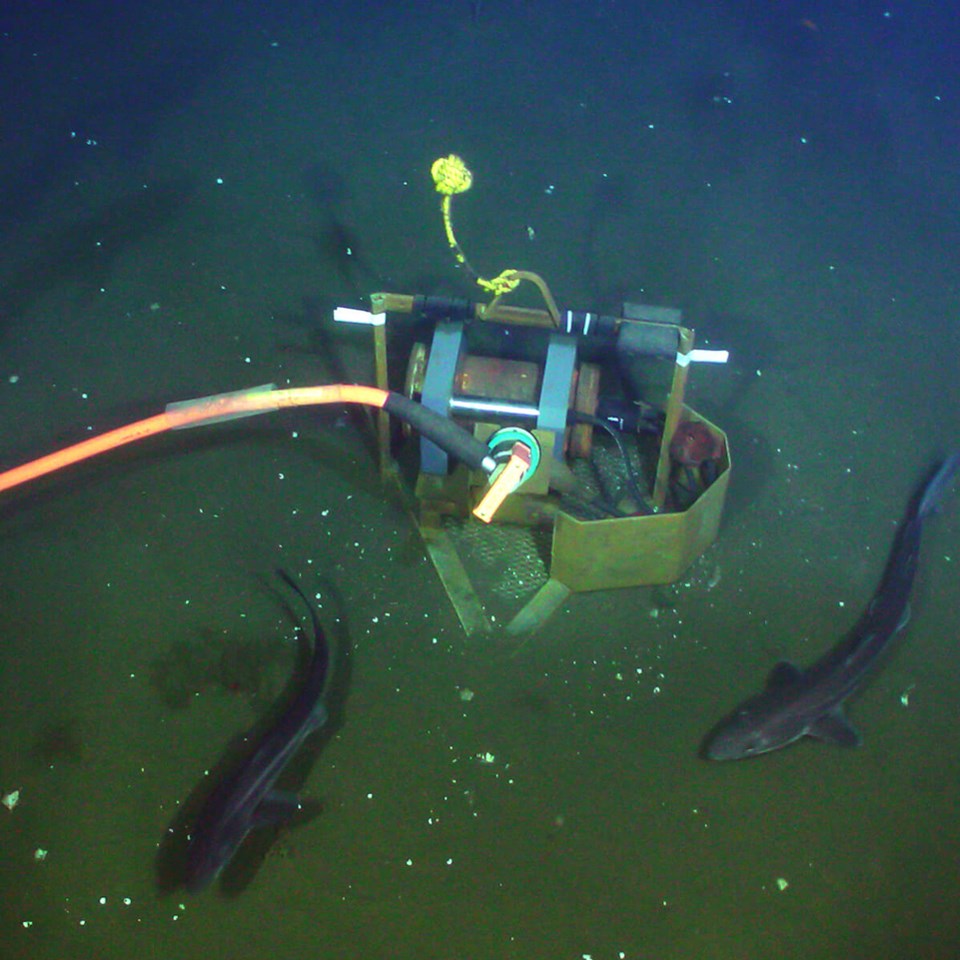

What if atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2)—a key, long-term driver of climate change—could be removed from the atmosphere and permanently stored as rock? It’s possible, thanks to a quirk of the Earth’s chemistry that makes CO2 react with ocean basalt to mineralize or take on solid form. UVic’s (ONC) initiative is at the forefront of developing technologies to do just that with its multipartner Solid Carbon project.

ONC is also positioned to provide support for other carbon-removal projects, says ONC president and CEO Kate Moran.

“We have real-time monitoring and sites in a wide range of ocean environments so our platform can be used to move these technologies from early stage or the laboratory into higher technology readiness and, ultimately, commercialization,” Moran says.

She notes the potential for durably sequestering up to 10 gigatonnes of atmospheric CO2 per year—a huge bite out of annual emissions.

Tracking change in the Arctic

is working with communities in the western Arctic—where temperature increases that are four times faster than the global average are rapidly transforming ecosystems—to better understand environmental change and its impacts.

Lantz’s research team uses a combination of field studies, remote sensing and collaboration with Gwich’in and Inuvialuit experts to determine where and why ecosystems are changing, and to understand how these transformations are impacting northern livelihoods.

“Landscapes are shifting so quickly that using conventional monitoring approaches to track change across large geographic areas is often insufficient,” says Lantz, “in my research group we have been fortunate to collaborate with hunters, fishers and trappers who are often the first to observe new changes.”

Lantz’s research is particularly relevant to northern decision-making and climate change adaptation because it identifies where ecosystem change is happening, but also explores the factors that control landscape sensitivity to warming. “Predicting what Arctic landscapes will look like in 50-100 years requires that we understand why we are seeing changes in some areas and not others,” adds Lantz.