Government support for mining critical minerals, increasing collaboration between industry and First Nations, and a growing demand for many of the minerals hosted in B.C. all point to momentum for B.C.’s mineral exploration and mining sectors.

That was the general optimistic note struck this year at the annual Association of Mineral Exploration (AME) Roundup conference, which drew 6,200 registrants from 41 countries.

The one big challenge that remains for those who go out looking for the gold, copper, nickel and other minerals that the world needs is capital. Who will finance mineral exploration going forward, now that institutional and retail investors are putting their money elsewhere?

Sources of financing for mineral exploration are changing, Roundup attendees heard. So if governments are serious about encouraging more exploration and development in critical minerals, they will need to address regulatory obstacles and may need to provide some financial support to help leverage private capital.

“The only way B.C. is going to be the powerhouse and mining and mineral exploration juggernaut it should be is we need to match, and probably exceed, that critical minerals funding that we see in Ontario, that we see in Quebec, that we see in Australia,” said Keerit Jutla, who replaced Kendra Johnston as AME CEO in September.

Roundup kicked off Monday with the announcement of phase 1 of a provincial critical minerals strategy. This follows the announcement of the federal government's $3.8 billion critical minerals strategy in December 2022.

The new provincial strategy has 11 key “actions” including the establishment of the Critical Minerals Project Advancement Office and the publication of a B.C. critical minerals atlas.

The Mining Association of BC (MABC) panned the strategy for its lack of fiscal policy. Mainly, the MABC is worried about the province’s new output based carbon pricing scheme and the disadvantage it will put B.C. miners at, compared to their peers in Ontario.

The AME generally welcomed the new provincial strategy, though Jutla said his association was hoping it would have also included $30 million for an equity investment fund for exploration.

“It demonstrates the government’s increasing support for mineral exploration and mining,” Jutla told BIV News. “That’s positive – we’re at least going in that direction. But, like in previous decades, there’s often a gap between how we get from exploration to a mine.”

In Quebec, an initial investment of $50 million through the fund has leveraged $105 million in direct investment in mineral exploration, Jutla said.

Something similar is needed in B.C., he said. He hopes to see the $30 million the AME has recommended for a critical minerals equity fund materialize in the next phase of the provincial critical minerals strategy.

The federal critical minerals strategy identifies 31 minerals deemed to be essential to the digital economy and the energy transition. Four of those minerals are currently mined in B.C., according to the new published as part of the new B.C. critical minerals strategy: copper, molybdenum, magnesium, and zinc. Copper is the most valuable critical mineral mined in B.C., which is Canada’s largest copper producer.

“Not on the 91ԭ�� list, British Columbia mines produce barite, gold, metallurgical coal (coking coal), lead, silica, and silver,” the new B.C. atlas notes.

“Aluminum is produced at the Kitimat smelter and lead, zinc, gold, silver, germanium, indium, and cadmium are refined at the facility in Trail. The province has near-term potential to produce nickel, niobium, platinum group elements (PGE), rare earth elements (REE), tantalum, and tungsten. It may also have potential for chromium, cobalt, fluorite, graphite, phosphate, tin, and vanadium as primary or accessory commodities.”

In a keynote address, 91ԭ�� Mining Hall of Famer Robert Quartermain – the man behind the Brucejack gold-silver mine – talked about Canada’s potential as a major producer of critical minerals.

He noted that 60 per cent of the world’s mining companies are headquartered in Canada, with 1,420 based in B.C. In total, these 91ԭ�� mining companies had a combined with a market cap of $320 billion in 2022, he said, and spent more than $4 billion globally on exploration that year. Of that, $740 million was spent on mineral exploration in B.C. in 2022.

“We are a powerhouse of global exploration and provide significant resources for the world,” said Quatermain, current CEO of Dakota Gold Corp. (NYSE:DC) and former CEO of Pretium Resources, which built the Brucejack mine that was acquired by Newcrest Mining in 2021 for $3.5 billion.

Quartermain noted three areas of growth that will drive the demand for all kinds of metals, from coper to rare earths – electric vehicles, cloud computing (which requires massive data centres) and electrification.

“With all this new demand for strategic metals, there’s a real sense of urgency to get these to market,” he said.

Whereas mining was viewed as an environmental liability in the past, attitudes have changed lately, including at the senior government level.

“I would say both federal -- current -- and provincial governments, since they took office, we’re now seeing positive narrative and support of industry and aspirations for better outcomes,” he said.

The industry still faces some hurdles, however, especially in B.C. One uncertainty in B.C. now weighing on the exploration sector is forthcoming changes to the Mineral Tenure Act.

First Nations have been successful in court in forcing the provincial government to look at amending the act in order to comply with the duty to consult with First Nations and get their consent for industrial activities taking place in areas where they may have rights and title. When anyone stakes a claim in B.C., First Nations want to be informed.

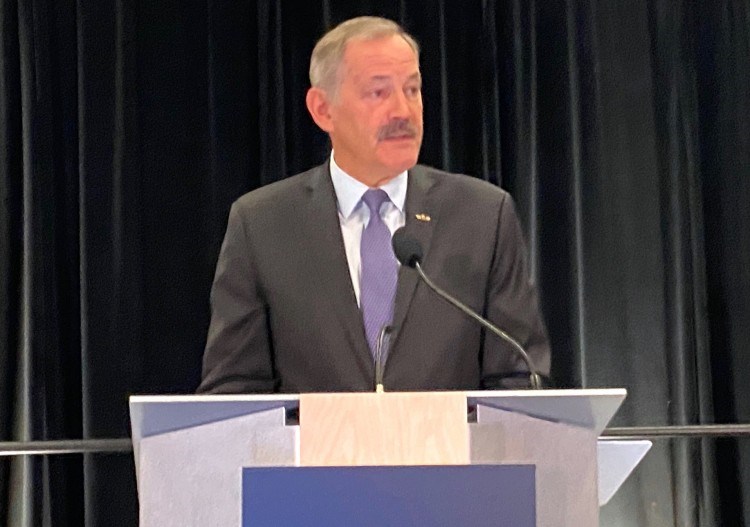

The court imposed a deadline to get the amendments done. In an opening speech Monday, David Eby told Roundup attendees that his government has 15 months to amend the act in a way that works for both First Nations and industry.

“We’re working together very closely, including with industry, to make sure that we’re addressing two concerns,” Eby said.

“One is that nations are full participants on the land. But also it needs to work. We are a mining jurisdiction. Prosperity for the nations, for the province, for the country, comes from mining. It has to work for industry as well.”