MINING.COM sat down In May with Dean Slocum, founder of Acorn International and Chris Anderson, a strategic partner at the Houston-headquartered consulting firm.

Slocum and Anderson offer ESG risk management advice for the extractive and industrial sectors around the world with dozens of projects that range from off-shore pipelines in Angola, bauxite mines in Brazil and gas infrastructure in Kazakhstan to gold mines in West Africa, to an oil company in India and offshore wind in the US.

Acorn’s work includes due diligence, capacity building, environmental and social studies and stakeholder engagement including through in-country partnerships and a network of experts.

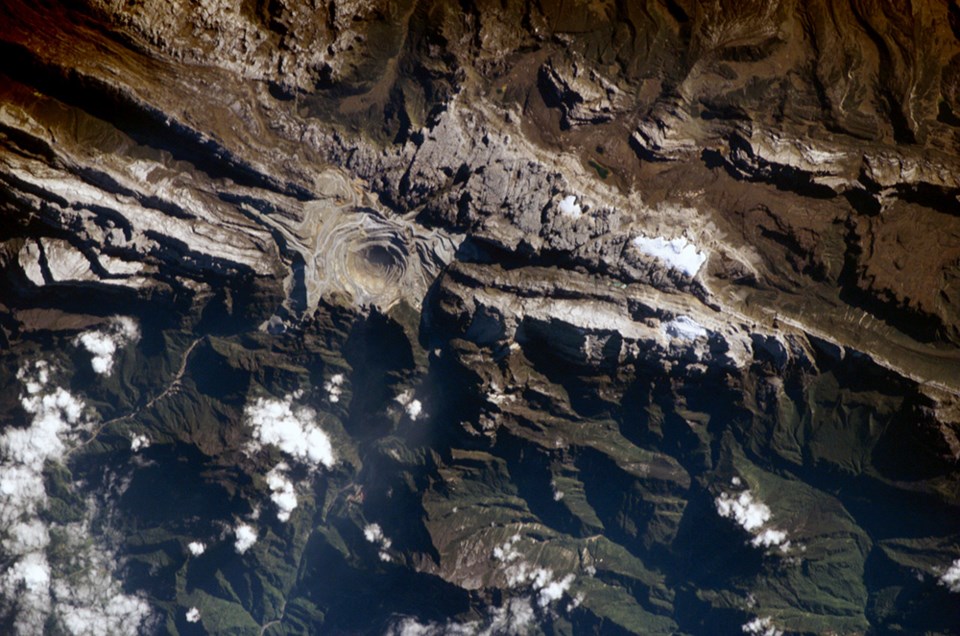

Emblematic Grasberg

Slocum, who has 30 years of experience in social, environmental and integrated hazard identification assessments (IHAZID), was due to depart for Grasberg, the iconic Indonesian copper and gold mine, and that’s where the conversation started. , operated by Freeport McMoRan in the mountains of West Papua, has been in operation since the 1960s and some 25,000 workers are on site.

The mine is in an area where separatist groups have long campaigned for the independence of the province and sporadic violence takes place to this day. Grasberg has other challenges too, including, to put it mildly, difficult terrain, remoteness, seismic activity, very high rainfall, and tailings issues.

Slocum says a complex operation like Grasberg is emblematic of the work Acorn does around the world:

“Operationally Grasberg is a very successful mine. Engineering and financial risks can be managed – it’s the societal risk, the community risks that are trickier to handle, but they’re not impossible, right?

“That’s Acorn’s business – applying the same kind of rigor with social science to these issues. It can be done reliably.”

Changing guard

Slocum says the mining industry is undergoing a changing of the guard and “the new guard gets it.” There is now an understanding that “We’re not going to be in business if we don’t do things that are the way of the host communities.”

Anderson, who has worked as a communities and social performance practitioner in the mining industry for 17 years with among others Rio Tinto and Newmont, is forthright about how the makeup of the industry has changed:

“When I joined Newmont 20 odd years ago and when I would be in the in an executive committee meeting or even a board meeting, I’d look around the room and there would – I have to be really frank here – they were all old, white fat men and you knew whether they were Americans or Brits or Australians or South Africans or 91įŁ┤┤s. They were all from the same mold.

“Today when I go into a meeting like that, more than half are women. I think it’s a major change marker and it’s something that’s pushing a different approach at the very highest level.”

Not the money

Anderson acknowledges some problems with the notion of ESG but takes issue with critiques, often from the right, that it is simply a woke concept and that it’s a “warm and fuzzy” issue:

“It’s not warm and fuzzy – it’s a business imperative. As an anthropologist, it’s the S that stands out for me. One of the misunderstandings that is so widespread within the industry, but also within governments is that this is really just about how much more you pay – whether it’s in the form of building hospitals and schools, or royalties and so on.

“The space between a community and its stakeholders is a critical one that has to be managed well, but one of the last things it’s about, is spending money.”

Juukan Gorge

In 2020, Rio Tinto destroyed caves at Juukan Gorge in West Australia that showed evidence of human habitation stretching back into the last ice age to make way for iron ore diggings. The blowback led to a clean out of senior management at the world’s number two miner.

Acorn recently completed a project for an undisclosed global mining company (not Rio) to roll out a heritage management system at all of its mines.

“I think a lot of mining companies were gunning for Rio – I can’t believe they did that! And then they go back to their operations meetings and say, you know what, that could happen to us,” says Slocum.

Rio was aware of the significance of Juukan Gorge, but says Slocum, “you have to go beyond awareness and understanding of heritage in the places you mine and make sure that you have the organizational structure in communication and resiliency to make decisions about these issues. “

Anderson believes with issues like these there is once again a generational shift: “I started working mining in Australia and as an anthropologist who’d spent years working with Aboriginal people, I speak two Aboriginal languages. In the early 90s, the [attitude] was if we saw an unusual rock formation, let’s just bulldoze it and not tell anyone about it, let’s just do it before it becomes a problem and look the other way.”

“But of course, nowadays the scrutiny with social media and the dramatic take up in Indigenous communities worldwide of cell phones has meant that nothing a mining company does is out of reach and observation anymore. [The concept of] cultural heritage has moved beyond stone axes and rock painting to intangibles like local languages and communities’ cultural lives.”

Slocum says ironically the Rio incident may actually cause some real positive developments by putting a spotlight on these issues.

Banks and shareholders

To the question whether much of the talk around ESG in mining amounts to little more than lip service or is there evidence of fundamental change within the industry, Slocum is ambivalent:

“There are some things that are happening that are forcing companies to do more of this. The GISTM (Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management), the Copper Mark, ASI (Aluminum Stewardship Initiative) are all initiatives forcing companies to do gap assessments to join the club, get the certification or the financing.”

“But is that a fundamental shift coming? I guess I would say the jury’s out on that. But I think it’s more than surficial.

“It’s probably not so much things like the Copper Mark, and it’s certainly not regulatory driven, but the lenders are really, really pushing some very meaningful change. [Lenders and shareholders] are saying it has to be sustainable because they’re going to follow up on it and say, well, we’re pulling our money out. And we’ve seen that in Brazil at a project we’re on right now.”

Anderson says it is significant – and somewhat surprising – that banks’ involvement in mining has evolved to the point where institutions “pull their money out because the project hadn’t achieved free, prior and informed consent from the Indigenous people. That’s happening right now.”

China in Africa

The role of Chinese investment in mining, specifically in Africa, has come under the spotlight in places like Congo and elsewhere. The DRC for instance has embarked on a program of revisiting and rewriting mining deals in the country made by Chinese companies, in one instance leading to the suspension of export licences for the massive copper and cobalt mine Tenke Fungurume.

While Western companies are heavily scrutinized and under pressure from their own shareholders and outside activist groups, the perception is that Chinese investors get away with environmental, safety and other breaches.

Slocum believes while some of it is overemphasized, much of the flak Chinese companies are getting is earned.

“It’s not across the board, but we have seen on the ground communities in Africa that have experienced kind of disproportionate and unnecessary environmental impacts from Chinese projects and there are also significantly lower employment of locals because companies use Chinese contractors and labour,” says Slocum.

Anderson adds, “doing things by the the book is delusional because the book is still being written and the fact that you follow the law is almost never sufficient in the S area of ESG.”

“I remember an African politician saying, well, , you guys come and you invest your money, but you have all these strings and you say you gotta do this. And we gotta do that. The Chinese just come and give us the money and then they get the contract and they do the work.

“But I, but I think a lot of African countries are regretting their open arms to China, which meant unfettered activity at the local level.”

Artisanal miners

The DRC is in many ways the nexus for mining and ESG and another issue that the industry has to deal with – and has not dealt with very successfully so far – is artisanal mining. Just the term itself is contentious – small scale mining may be a better description. Or simply illegal mining.

Anderson, who is past chair of the International Council on Mining & Metals (ICMM) Human Rights and Indigenous Peoples Working Group, says there’s a discourse that has small scale miners as “romantic heroes” as if they are “up against the big miners who are stealing all the ground that they could normally make a living from. He says that in West Africa, where he worked extensively as Newmont’s external affairs director, in countries like Guinea, Liberia, Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire, small-scale mining is organized crime and in most cases it’s not even locals that are involved.

“In many cases, they’re roving gangs and it’s increasingly done with Chinese money, and even Chinese nationals themselves are involved in these activities. In places like Ghana, where Anderson lived for six years, there is a growing realization by the government and citizens that illegal miners have contaminated just about all the waterways in the country for their own criminal activity.

I think it’s estimated that something like 30% of Ghana’s gold production annually leaves the country without any taxes or royalties because it’s done through small-scale and mostly illegal mining.”

Even when official channels are used, small scale mining is ripe for abuse. A 25-year deal published last week by the DRC that hands a little-known UAE firm exclusive rights to export artisanal gold at preferential rates raised eyebrows.

On the opposite side, the formal mining companies complain that small-scale miners infringe on their concessions, and they get blamed for pollution and other issues like influx of crime and other illicit activities around these mines.

“Big companies often refuse to deal with it because they say, look, this isn’t our country it’s up to the government to do. And the ICMM tried valiantly about 10 years ago to bring together small miners and large miners, and there was a guidance note produced which I was involved in. But basically, most big miners haven’t realized how to deal with it, and I’m not sure anybody has fully, except to have the government send the military in and burn all the equipment and to jail the people and so on.

“African countries have to ask ‘do we want large scale anarchy as we can see in eastern DRC, or do we want a well-regulated investment with big miners wherever they come from, who knows what they’re doing in terms of environment management and the community?”

Slocum thinks the Glencores of the world that are willing to go into an environment like that will apply consistent standards anywhere they work, depending on local conditions of course.

“But It takes a lot of probably hard gut checks to decide – is this what we want and if we’re in the country already do we want to stay there?”

Greenwashing

The exponential growth needed in mining as a result of booming demand during the energy transition will inevitably bring greater awareness of the industry among the broader public.

Mining is a tiny industry compared to global oil and gas – Saudi Aramco has a larger market capitalization than the 100 biggest mining companies in the world. But thanks to electric cars mining is stepping out of Big Oil’s shadow and the vast NGO and environment protestors complex is taking notice. Is Big Mining ready?

Slocum says Acorn International is working with Rio Tinto and others in Guinea following a series of community complaints against Compagnie des Bauxites de Guinée (CBG) in which Rio Tinto and Alcoa have a majority share and the state has 49%. The complaints have reached the ombudsman of the World Bank and International Finance Corporation (IFC) for mediation.

“They are hesitant, as are many, to make their case known better because they’re going to be seen as greenwashing or white washing.”

Slocum believes the NGOs and lawyers acting on behalf of the community are casting them as the big bad company and instead of embarking on a charm offensive about the good that they are doing in the community, the miners “are just by putting the facts out there – the good and the bad.

“I think it’s a guarded industry and that’s good. In the past there’s been too much whitewashing and greenwashing, and I think there’s a feeling now like we don’t want to get too far out ahead of that. But they are catching a lot of flak as a result.”

“These NGO, they’re smart, they’re going after the money chain. So now it’s the car companies that are putting pressure on miners,” says Slocum.

Anderson says in his experience in the developing world it’s the other way around: “The nationalized mining companies are the ones that drive over the locals, especially when they’re of a different culture or a marginalized group of people.”

Going mainstream

The Guinea bauxite story reached the mainstream media in the US, with the Washington Post running a major feature on it last month. You can also read about cobalt mining in Vanity Fair (“too dirty even for Elon Musk”) and iron ore mines in the New Yorker, and car companies getting into mining per NPR as publications search for a new blood diamond narrative.

Miners seem unable to counter these narratives effectively:

“And the David vs Goliath story may be a hackneyed one, but it’s also what the public kind of buy into. Look at these big corporations – they’ll do anything for profit and run over the little guy,” Anderson says.

And, says Anderson, the David vs Goliath angle is also a cop-out by journalists because rather than dipping into the facts journalists prefer to pre-empt “any accusation that they are paid off by the company if you say anything good about them.”

Anderson believes mining is in some ways unfairly picked on, “because we dig big holes in the ground.”

“That said there is also an internal industry problem. Mining is a technical discipline and mining people are not very good at communicating with the outside world.

Mining everywhere

Recently Anderson, who is also research associate at the Colorado School of Mines, was speaking at the University of Denver in the School of Theology “of all things”, and about 40 students, some of whom were older, “ended up having an amazing debate about mining.”

“When I talk to this sort of crowd, I would say look around the room – every single thing that’s not wood came out of a mine. Everything. So we don’t even have to just look at critical minerals. We cannot live the way we live without mining.”

While making the case for mining being essential to daily life is not difficult, Anderson does not believe this is the message to take to the public. The approach should be more localised:

“But that’s not to say we need to talk about it more. You need transparency where you develop ways so that stakeholders – not talking about shareholders here – can see for themselves how they will benefit and become advocates themselves.

“In many parts of the rural and remote areas of the developing world, mining is the only chance for any economic investment that’s going to lift people out of poverty.”

NGO-industrial complex

The role of NGOs, a vast sprawling network of often well-funded activist organisations, in mining is only growing and in downtown 91įŁ┤┤, where hundreds of junior miners maintain offices (or at least addresses) encountering the odd protest especially during warmer weather is not infrequent.

One such event MINING.COM saw featured two community members from an early stage project in Mexico flown into 91įŁ┤┤ by a New York-based NGO to hold banners and bang drums outside the developer’s offices.

The scene outside the office was in stark contrast to video and images shared by the company showing one of several townhalls attended by 3,000 people from the local community where broad support for the project was given.

“I’ve seen it myself many times, especially in my years at the corporate office in Newmont, where we’d have an AGM that was open to anybody, not just shareholders –and the NGOs would bring one or two people from the areas where we worked, who would spin this narrative about death and destruction.

But even in this arena, Anderson sees positive changes and a future that may be less antagonistic than before.

“I worked for Newmont CEO, Wayne Murdy, and in my first few months he agreed to go to Toronto to take part in the mining and minerals for sustainable development event, which marked the beginning of the International Council of Mining and Metals and brought together CEOs of all the major mining companies and senior staff with all the major NGOs.

“I tried to organize a meeting between Murdy and some of these NGOs, and almost none of them would. They didn’t want to hear any story that went up against their prejudices.

“These days, several of those people and one of the leading lights in the mining critique business 20 years ago are now working for an NGO that’s incredibly constructive. Tough critiques but working towards a joint aim with mining companies. The most recent example that we’ve worked hard on is free, prior and informed consent for Indigenous peoples in Suriname where an NGO organized an independent group to facilitate the FPIC process.”

“That kind of partnership is getting more and more common, but [some of the reluctance] also comes from miners who say ‘I’m not going to deal with an NGO. They don’t like us. They lie.’ You know, they’re disingenuous and we still see examples,” said Anderson referring to the Guinea mediation Acorn is involved in where one of the NGOs openly admitted that “the reason they didn’t want to go along with solutions was that it would stop their funding.”

But, says Anderson, mining companies are becoming less averse to working with NGOs and there’s a growing realization that “it’s probably only 10% or 15% of the NGO world that are activists” and the rest of them are focused on genuine advocacy and development help for poor communities.

U.S. mining resolutions

As for the megatrends of the moment – the green energy transition and electric cars – how will that affect the broader mining industry?

“I was a carmaker, I’d be very worried about the supply chain right now.

“One of the interesting bellwethers of the trend is going to how the Biden administration approaches things like the Resolution Copper, a project which is in the top three worldwide unexploited copper deposits right here in our backyard.”

Discovered in 1995, the Resolution deposit in Arizona contains over 10m tonnes of copper and from an environmental Resolution ticks the boxes: It’s an underground high-grade mine using the latest block-cave technology that shrinks its environmental footprint.

The world’s number one and two mining companies, BHP and Rio Tinto, have already spent $2 billion on Resolution, including reclamation of a historical mine. It was a pet project of late senator McCain and Resolution had the backing of both Obama and Trump.

But Biden (temporarily) blocked it early on in his administration and just last month the timeline for approval was again up in the air after the US Forest Service said it does not know when it could produce its review, which is crucial to a land swap with Native Americans on the site of the proposed mine.

Three things

“In the 40 years I’ve worked with Indigenous peoples I have never met an Indigenous person that’s against mining. They want economic development because almost always they’re marginalized by mainstream economies.

But there are three things that have to be met:

“If they’re going to support you, one is that they have a say in the decisions about the project that affects them. Secondly, that the environmental and cultural aspects are looked after and respected and that doesn’t mean to say that there’s not a room for compromise. But thirdly, that they and their descendants benefit financially from it.

“If those three conditions are met, you’ve got very strong supporters there in whatever stakeholder the Indigenous people belong to.

And I think a lot of mining companies haven’t really twigged to the fact that you can get very strong local support if you bring them in on significant decision making.”