91原创 salmon farmers are posting improved sustainability metrics, says a new industry report, including lower escapements, reduced use of pesticides and antibiotics, and improving mortality rates.

Not that that probably matters much for B.C., where open-net salmon farming is being shut down by the federal government.

But it may still matter for Atlantic Canada, notably Newfoundland, where salmon farming may still have potential for growth.

The 91原创 Aquaculture Industry Alliance (CAIA) has released its first on 91原创 salmon farming that emphasize some the progress salmon farmers have made on everything from greenhouse gas intensities to feed ratios.

“All the companies that we’re working with, they have sustainability reporting internally,” CAIA president Timothy Kennedy told Business in 91原创. “The companies in British Columbia, for instance, the big Atlantic salmon farming companies – Grieg, Cermaq and Mowi – all do global sustainability reports.

“What we didn’t have in Canada is … a 91原创 performance report that could help 91原创s understand what is happening with the performance across salmon farming, across the country.”

The CAIA’s first sustainability report notes that, pound for pound, salmon farming has the lowest carbon footprint of any farmed animal species. It also has the most efficient feed conversion ratio of any farmed animal. The report notes that 91原创 farmed salmon has a feed conversion ratio of 1.2 kilograms of feed to one kilogram of fish.

By contrast, the feed conversion ratios for beef is six to eight kilograms per kilogram of beef.

Some of the biggest concerns that environmentalists have with salmon farming is the impact farmed fish may have on wild stocks, including fish escapes and disease and sea lice transmission.

Fish escapement in B.C. is not as big a concern as in Atlantic provinces, since the Atlantic salmon raised in B.C. are genetically distinct from 91原创 salmon and therefore cannot breed.

In Atlantic provinces, escapements of Atlantic salmon may be more of a concern, as potential hybridization could occur if farmed and wild Atlantic salmon were to breed.

“Fish escapes are at an all-time low,” Kennedy said. “We’re talking about a couple of hundred across Canada. That’s significant.”

The report notes improvements in feed efficiency, thanks to technology.

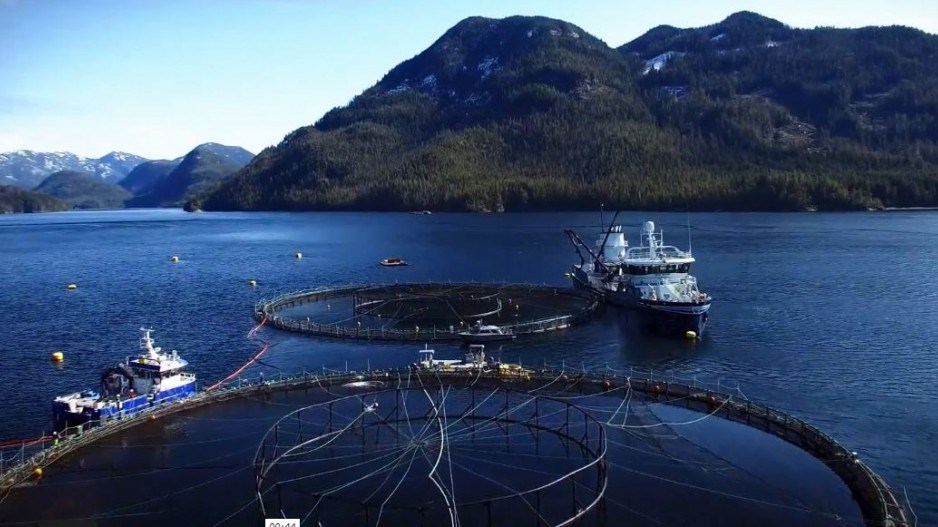

“All net pens across the country now have cameras and monitoring systems in the net pens,” Kennedy said. “That’s really focused on feed efficiency – really reducing the amount of wastage from the net pens. And really that feed efficiency is the best of any large-scale animal production in the world.”

Farmed salmon are vulnerable to predators, pests, algal blooms, and low oxygen events, all of which can reduce survival rates and reduce productivity. The report notes that the current survival rates are 82 per cent.

“That’s not far off the global average, but it’s not where we want to be,” Kennedy said. “We want that up to 90 per cent.”

As for concerns about the spread of disease and lice from farmed to wild salmon, some open net salmon farmers have been experimenting with hybrid and semi-closed containment systems, which reduce the exposure of wild fish to farmed fish. Kennedy pointed to Cermaq’s semi-closed containment system in Clayoquot Sound as one example.

“We need to continue looking at those and looking at ways of investing in those all across the country – not just in British Columbia,” Kennedy said.

There are other promising technology approaches that might further address things like fish health and disease transmissions, though Kennedy points out these technologies require investment, and the investment climate in B.C. has become uncertain, given the Liberal government’s plan to phase out open-net salmon farming altogether by 2029.

Kennedy said AI and high-tech monitoring offers the potential for individualized fish health in net pens -- something that might reduce risks of disease from pathogens by allowing individual fish identified as sick to be removed from open-net pens and treated.

“With the right signals around these things, there could be a lot of technology moving very quickly to improve fish health, which would reduce any risk to wild fish,” Kennedy said. “We could improve fish health by 80 per cent very quickly, if there was the right environment to do so in the net pens.

“That is not a big stretch because that technology exists right now. The problem is we don’t have the capital and the confidence in it right now, especially in British Columbia.”

Up until about five years ago, B.C. accounted for 60 per cent of Canada’s salmon farming production, with the Atlantic provinces accounting for 40 per cent. But starting in 2020, the federal government began shutting down salmon farms in the Discovery Islands region, which resulted in the loss of 25 per cent of production in B.C.

The Trudeau government’s goal is to have all open-net salmon farms phased out by 2029. The federal government’s transition plan envisions replacing open net salmon farms with land-based farming or ocean-based closed containment – all of which requires investment in technology.

But thanks to the federal government's policy, the salmon farming industry is no longer investing in B.C. Since the Trudeau government's plans to phase out open-net salmon farming applies only to B.C., Atlantic Canada may hold more promise for the salmong farming industry in Canada.

“It’s actually growing a bit in Atlantic Canada, but it’s declined in British Columbia,” Kennedy said. “And, of course, the risk of the Liberal commitment to ban open-net salmon farming in B.C. by 2029, we’re still seeing no additional investment in British Columbia right now.”

The one region of Canada that may be poised for growth is Atlantic Canada.

“Newfoundland in particular has some real growth opportunity,” Kennedy said.