Protected forests hailed in B.C. as a haven for biodiversity have been logged to the point where less than a third of the total area contains old-growth trees, a new report has found.

The , from the B.C. chapter of the 91原创 Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS), found 29 per cent of the area contained in legally protected Old Growth Management Areas (OGMA) actually have old-growth forests on them.

Active cutblocks, meanwhile, were found to overlap on more than 27,000 hectares of land designated as an OGMA, an area more than double that of the City of 91原创.

Designated by ministerial order, the class of protected forest accounts for six per cent of the 11.4 million hectares of old-growth forests still left in the province.

As the B.C. government moves to protect 30 per cent of its land base by 2030, the latest findings suggests it is overestimating how much is really protected, according CPAWS’s conservation research and policy coordinator Meg Bjordal.

“They're intended to protect rare, at-risk biodiverse old-growth forests. As well, they're being used to count towards B.C. and Canada's biodiversity targets,” said Bjordal, who authored the report.

“It’s inflated accounting.”

The B.C. government considers most coastal forests as old growth when trees reach 250 years old; in the drier Interior, the old-growth threshold is often set at 140 years old.

Less than half of old-growth forests that existed in B.C. before the Industrial Revolution still stand today, according to B.C.’s .

Rachel Holt, an independent forest ecologist who served on the panel, said the low share of old-growth trees in OGMAs is emblematic of a forestry paradigm that has been haphazardly applied since the mid-1990s. At the time, the management areas were as a key strategy to ensure enough old-growth stands from across B.C. were protected to serve the province’s forest ecosystems, she said.

But in the nearly three decades since, “we flipped it around and put timber first,” Holt said.

“We have said for a long time that that is an illegal situation.”

Logging incursions shrink areas meant for old growth

When a ministerial order legally designates a piece of land as an OGMA, the area is required to be put into forest landscape or stewardship plans. But the report found that those original plans are often flawed from the start.

In one example, the report points to the Campbell River Natural Resource District on 91原创 Island — a highly productive forest ecosystem where the share of old-growth forests is double the provincial average.

Bjordal said she found that over the last 40 years, harvested cutblocks have overlapped with about 3,000 hectares of the Old Growth Management Areas — an area equivalent to more than 2,100 soccer pitches.

Across the province, another 12 per cent of land designated as OGMA are some combination of lakes, rocks or alpine areas with no trees and little biodiversity.

That means Old Growth Management Areas are essentially counting thousands of hectares of land as areas of rich biodiversity when on the ground they are often immature forests or completely devoid of trees.

“You probably wouldn't expect 100 per cent old-growth forests because you're going to have some natural areas of maybe rocks or ponds, or things that you would expect in a natural landscape,” Bjordal said.

“But the issue is when you have a really small proportion of intact forest as well as patchy areas that just don't serve biodiversity.”

To make matters worse, Bjordal said logging companies can apply to amend the borders of OGMAs so they can access timber. That has left many of the ostensibly protected areas as “misshapen and narrowed” versions of what they used to be.

In the Campbell River region, active logging areas cut into 284 hectares — more than 200 soccer pitches — of forest legally designated as Old Growth Management Areas.

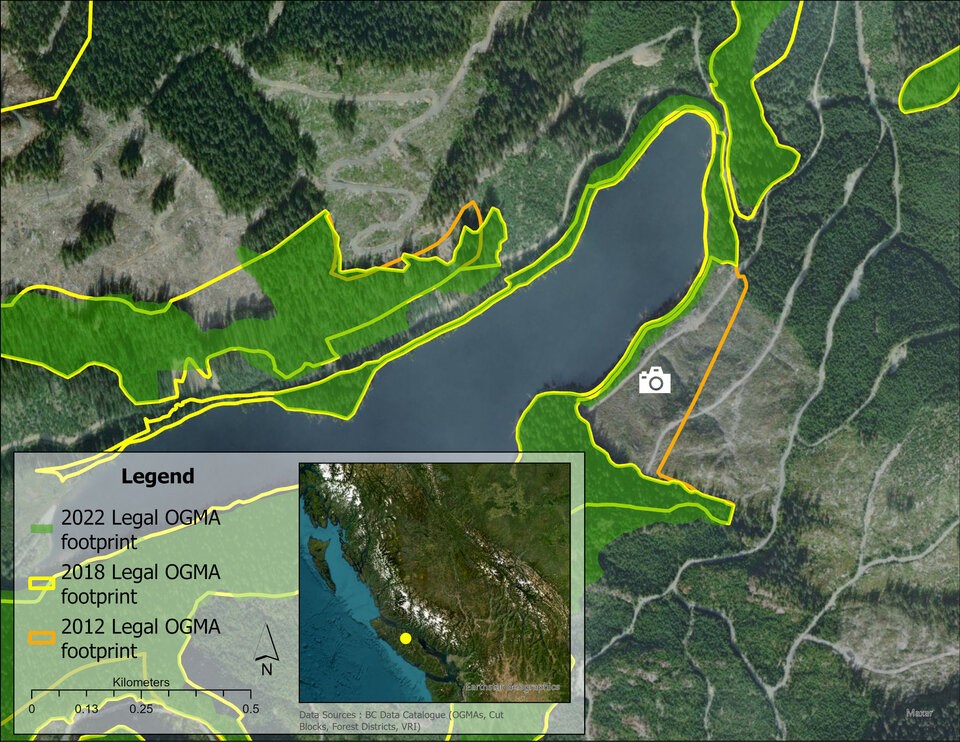

One section of forest near Stewart Lake on 91原创 Island used to sit within the boundaries of an OGMA. But in 2012 and 2018, regulators approved its removal, and by 2022, it was logged.

In B.C.’s Selkirk region, Holt said she has been raising the undercounting of old-growth forests for a decade. Her research prompted a provincial analysis, which in turn found roughly 20 per cent of OGMAs in the region were old growth, far below the provincial average, Holt said.

“I’m not surprised where we’re at because we’ve done this very purposefully. Now, we’re noticing because of the biodiversity and climate crises.”

B.C. 'violated' federal and international protection standards

Bjordal said her team was not prepared for the gap between what the province was reporting to the federal government and what was actually happening on the ground.

“It was definitely unexpected,” she said.

She said that for B.C.’s protected areas to be counted towards federal and international biodiversity targets, certain criteria must be met. That includes long-term protection, a prohibition of activities that threaten biodiversity, and that the areas facilitate biodiversity.

“All of our findings indicate that most of the standards for being reported as counted are actually violated,” Bjordal said.

Bjordal said the B.C. Ministry of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship agreed to meet with CPAWS after it shared a copy of the report.

In an email to Glacier Media, a spokesperson for the ministry acknowledged many OGMAs contain a minority share of old-growth forests.

The province has “paused further reporting” on Old Growth Management Areas as it works on a “new assessment approach,” said the spokesperson.

“The province is reviewing and strengthening OGMA management as part of its improvement of forest management across B.C.,” read an emailed statement from the ministry.

“Factors including a changing climate, insect outbreaks and B.C.’s catastrophic wildfires are all important reasons for reviewing the policies that help us manage our old forests.”

The ministry pointed to a number of recent funding announcements as evidence it is working with First Nations to develop “long-term strategies for old-growth management.”

According to the CPAWS report, any revised guidelines for Old Growth Management Areas should be amended to ensure they “predominantly” contain old-growth forests. Such amendments should also guard the areas against incursions and fragmentation from clear-cuts and road building, the report notes.

If B.C. can’t make those changes, the OGMA should be removed from Canada’s ledger of protected areas and be replaced with something that protects what old growth is actually there, Bjordal added.

“I think it's important for people to know that areas that B.C. is currently claiming is protected aren't actually protected,” she said.

“We need to hold the government accountable.”