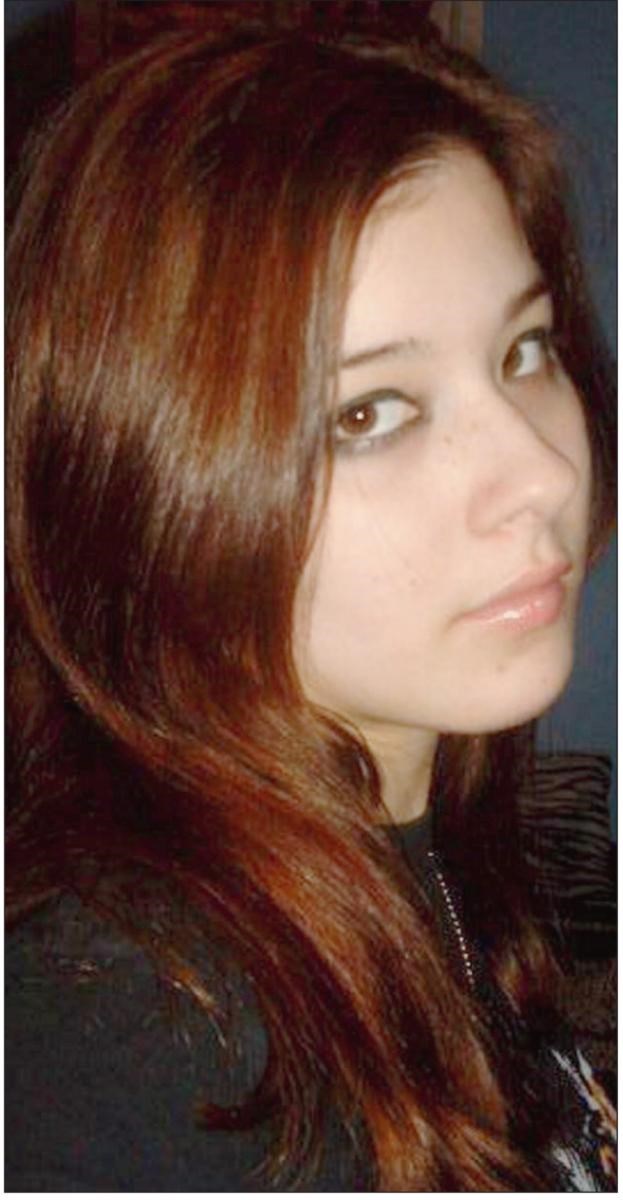

When it turns out monsters have been walking among us, we struggle to understand. Our hearts break for those they have hurt so terribly. Not just Kimberly Proctor and her family and friends, but all those who have been devastated by the horrific crimes committed by Kruse Wellwood and Cameron Moffat.

The facts are nightmarish. And the nightmare is made worse by the young men's callousness -the laughter and joking revealed in tapes made as they were transported in a police van, their casual and relaxed attitude in talking about the crimes and their intention of killing again.

It is understandable to want simply to look away. And for some, that might in fact be the only possible response.

But as a society, we need to pay attention. That's why the Times 91原创 applied successfully for the release of the exhibits and evidence presented in court. The materials are shattering. But they are also important in helping us, as a community, develop a response. And that is why we chose, after much internal debate, to present much -but far from all -of that information. This is not a time to hide from the facts.

Kimberly Proctor's family showed great courage in calling for the release of all the evidence. It is important, they said, that people really understand what happened and who Wellwood and Moffat are.

We are a long way from that understanding. The two are, according to court reports, psychopaths. They have shown no remorse or empathy and successful treatment is unlikely, the reports found. They will pose a danger for up to 40 years, long after they are eligible for parole.

We know that psychopaths -people with no moral compass or empathy -take a terrible toll. Estimates suggest they make up 15 per cent to 25 per cent of the North American prison population. Many others live among us.

But our understanding is limited and research lags far behind the efforts put into other mental illnesses.

Researchers believe there is a genetic component -which certainly is reinforced by the fact that Wellwood's father committed a similar crime, raping and killing a 16-year-old girl. But upbringing and life experiences also appear to play a role.

We can test for psychopathy -an effort pioneered by Robert Hare of the University of British Columbia. But recognizing behavioural symptoms or effective treatment remain elusive.

There is no point in assigning any blame, except to the killers. But we can and should look fiercely for any lessons that can be learned.

Both Wellwood and Moffat showed disturbing behaviour at early ages. Moffat acted violently to his family and other children as early as five. He was suspended from middle school and expelled from high school for bringing a weapon. He kicked the family dog violently enough to injure it. Wellwood struck his mother and assaulted other students. Both began drinking at 10 and used a variety of drugs and developed a fascination with sexual sadism.

And by elementary school, they had found each other and become friends.

It's a record that raises questions. Are our schools adequately prepared to identify behaviour that hints at future, more serious crimes? What happened each time Wellwood or Moffat broke the rules or committed violence? Did family, or their classmates, see the risks? Are the resources, in schools and in the community, adequate to provide assessment and treatment? Was help available if it was sought?

And, perhaps most difficult, what do we do when treatment does not work?

It will take great courage to face this crime and answer these questions. But it is our duty.