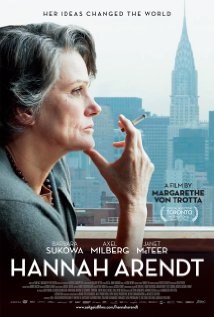

Margarethe von TrottaŌĆÖs new film ŌĆ£Hannah ArendtŌĆØ has reignited an emotionally charged and important debate that has raged since cultures been aware of the violence that characterizes so much of human behaviour.

How are we to account for the evil actions frequently perpetrated by human beings?

Political thinker Hannah Arendt raised the question in 1961 when, after attending the trial in Jerusalem of Nazi Adolf Eichmann, she wrote five articles for the ŌĆ£New YorkerŌĆØ that were published in 1963 as the bookEichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil.

Scholars have generally agreed that, in attempting to understand EichmannŌĆÖs evil acts, Arendt came to see him as an ordinary man who was committed to his work and determined to be obedient to the authorities who had entrusted him with the responsibility to fulfill their demands. ┬ĀEichmann was not a deranged monster; he was a man doing his job with unquestioning fidelity to the ideology to which he had committed himself and to those under whose authority he operated.

The chilling implication is that, given similar circumstances, most ordinary human beings would be capable of acting as Eichmann acted.

But recently scholars have suggested an even more frightening view of ArendtŌĆÖs work.

Roger Berkowitz, director of The Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and the Humanities at Bard College explains that ArendtŌĆÖs insight ŌĆ£is not that Eichmann was just following orders, but that Eichmann was a ŌĆśjoinerŌĆÖŌĆØ.

Berkowitz quotes EichmannŌĆÖs own words when, in an attempt to explain his behaviour the Nazi bureaucrat who efficiently orchestrated the extermination of millions of Jews, claimed he found it impossible, ŌĆ£to live a leaderless and difficult individual life,ŌĆØ in which ŌĆ£I would receive no directives from anybody.ŌĆØ

In her film Margarethe von Trotta avoids obvious identification with any position in the debate about the source of EichmannŌĆÖs evil deeds. But, in a subtle way, the film aligns itself with the suggestion that Eichmann acted as he did out of a perverse need to belong.

If in fact EichmannŌĆÖs deeds were motivated by his determination to be a ŌĆ£joinerŌĆØ, he could not have been more different than Arendt as von Trotta portrays her. Throughout the film, Arendt appears in splendid isolation. She is frequently seen alone, apparently struggling with her response to Eichmann. After ArendtŌĆÖs articles are published, von Trotta shows Arendt being abandoned by all the institutions that had previously supported her work. Yet Arendt refuses to back down or to compromise what she has come to believe is the truth.

Von Trotta made an interesting choice in her decision to have Eichmann appear in the film through black and white archival footage of his actual trial rather than using an actor. There are moments when EichmannŌĆÖs face fills the screen forcing the viewer to confront the presence of this man who has so come to embody the evils of Nazism.

Von Trotta seems to be suggesting that, like Arendt, we must all wrestle with our response to the presence of evil behaviour in the human community. She refuses to allow us to escape the responsibility of personal conscience.

For anyone who works in an institution von TrottaŌĆÖs film offers a profound challenge. Institutional commitment must never displace the responsibility of personal conscience. Institutions exist, not to do peoplesŌĆÖ thinking for them, but to challenge us to take responsibility for our choices and actions.

Evil occurs when, in the interests of belonging, individuals give up their responsibility for doing the hard work of making difficult personal choices and living by their deepest convictions.┬Ā

Christopher Page┬Āis the rector of St. Philip Anglican Church in Oak Bay, and the Archdeacon of Tolmie in the Anglican Diocese of B.C. He writes regularly at:┬Ā

Christopher Page┬Āis the rector of St. Philip Anglican Church in Oak Bay, and the Archdeacon of Tolmie in the Anglican Diocese of B.C. He writes regularly at:┬Ā

You can read more posts from our interfaith blog, Spiritually Speaking