In 2019, humanities student Teresa Sammut, writing in the University of Victoria’s Martlet student newspaper, wrote an article entitled “Thoughts on the decline of a ‘human’ education.”

“The humanities encapsulates the study of human experience through the eyes of humanity itself,” wrote Sammut, then a humanities student herself, adding: “Its continued value is shown through an ever-changing participation in reshaping the global community at large.”

Those thoughts echoed a 2016 a Universities Canada paper entitled “The future of liberal arts.” (For the purposes of this column, I’m using humanities and liberal arts as interchangeable terms for the same kind of university education.)

Universities Canada is a non-governmental, membership-based organization governed by a board of directors consisting of university presidents.

The 2016 paper emphasized that employer demand for the skills and abilities developed through the study of literature and history, to name just two components of a humanities/liberal arts program, is growing.

That’s because, according to this group of university presidents, “in an increasingly complex, multicultural and technologically advanced world, employees need knowledge, skills and adaptability that are integral to an education in the humanities and even the social sciences.”

So what’s happening to 91ԭ�� university humanities courses, which have seen an average decline in liberal arts enrolments of 20 per cent in recent years?

That decline is neither new nor unique to Canada.

In 1977, Donald L. Berry, a professor of philosophy at Colgate University, a private liberal arts college in Hamilton, New York, explained the decline this way: “Many students and their parents now seek a clear and early connection between the undergraduate experience and employment. “

In the rush to employability as soon as possible, students in pursuit of an undergraduate degree may have forgotten that a humanities degree can also, in the mid-term of a career, deliver career flexibility, adaptability and innovative thinking — all increasingly valued by employers in the 21st century.

According to Kathy Wolfe, vice-president for integrative liberal learning and the global commons at the Association of American Colleges & Universities, “a liberal arts education is more likely to provide the skills and experience to innovate and adapt in an economy where, on the average, some graduates will change jobs 15 times before they retire.”

“Employees who are too narrowly specialized are not ready for that economy,” Wolfe writes.

Of course, it may be that declining program enrolments and misconceptions about humanities graduates’ employment prospects have created a false-crisis narrative.

Even so, participants at the 2016 Universities Canada workshop agreed that there may be some urgency for universities and arts faculties to better rebrand and communicate the value of a liberal arts education and to reframe its relevance in today’s diverse society, with its innovative economy.

According to another study — a 2016 study by the Business Council of Canada — Canada’s largest employers increasingly value soft skills over technical knowledge.

The soft skills most often listed as desirable by employers include relationship-building, communication and problem-solving skills, teamwork, and analytical and leadership abilities — attributes developed and honed through studies in the social sciences and humanities.

And there is another side to a humanities degree, beyond employability readiness.

Workshop participants also spoke about the role of the liberal arts in broadening intercultural awareness and fuelling creativity. They highlighted the vital contribution of the liberal arts in preparing students to tackle Canada’s most pressing problems, including the national project of reconciliation with Canada’s Indigenous peoples.

The real value of humanities courses, taken as a whole, is that they encompass the full scope of human thought, including creativity, languages, religion, philosophy and the broad spectrum of the performing arts and the visual arts.

Humanities education explores the commonalities and differences in self-expression that humans have exhibited through the ages and continue to demonstrate today.

In short, humanities programs expose students to diverse ideas from around the world, broadening their knowledge and developing their critical thinking abilities.

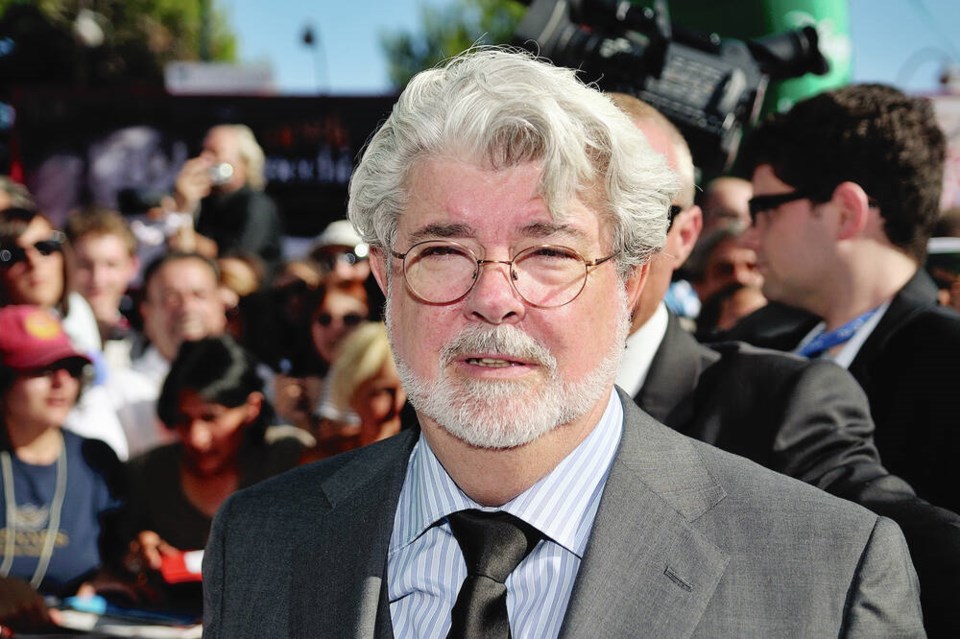

Star Wars director George Lucas said of the humanities: “The sciences are the ‘how,’ and the humanities are the ‘why’— why are we here, why do we believe in the things we believe in. I don’t think you can have the ‘how’ without the ‘why.’ ”

The broadly applicable skills that the liberal arts/humanities provide also directly benefit individuals in their personal and professional lives.

As American philosopher and law professor Martha Nussbaum notes, “Business leaders love the humanities because they know that to innovate, you need more than rote knowledge — you need a trained imagination.”

Geoff Johnson is a former superintendent of schools.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]