In the aftermath of two horrendous child deaths, Mitzi Dean was demoted from her position of minister of child and family development.

In Chilliwack, an 11-year-old Indigenous boy was tortured, beaten and ultimately killed by his foster parents. The boy’s eight-year-old sibling was also extensively abused in a manner that passes comprehension. Since the ministry’s social workers failed to make the routine visits required of them, the responsibility ultimately rested with Dean.

The second death, however, occurred in somewhat different circumstances.

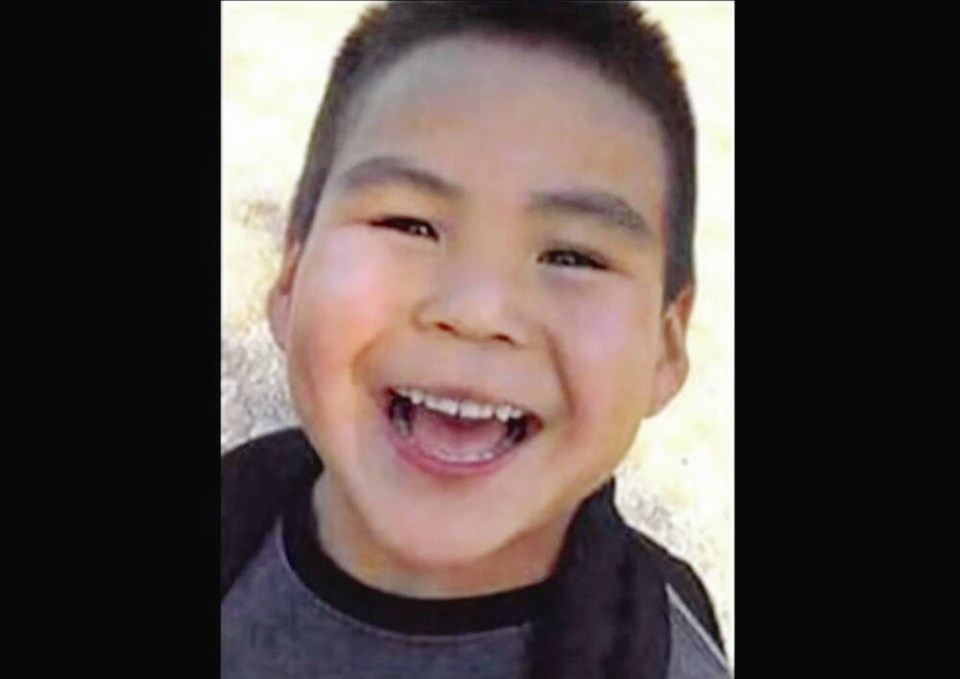

In 2018, Dontay-Patrick Lucas, a six-year-old Indigenous boy from Port Alberni, died at the hands of his mother and stepfather. Both parents were initially charged with first-degree murder, but eventually pleaded guilty to manslaughter last November.

This case differs from the Chilliwack case, however, in that the young boy had been in the care of the USMA Nuu-Chah-Nulth Family and Child Services agency. It was the agency’s decision to place the child with the parents who killed him.

Moreover the Child, Family and Community Service Act stipulates that when a child is of Aboriginal birth, and an Indigenous care agency is available, the child should be placed with the agency.

There are two points of concern here.

First, it’s not clear how Dean was responsible for this child’s death, since by law the case had been transferred to the Nuu-Chah-Nulth agency.

More important, delegation arrangements of this kind are likely to grow in number. Twenty-four Indigenous child and family service agencies have been established across the province, and 117 First Nations either have, or are actively planning, such arrangements.

In many respects, that’s both understandable and appropriate. There is distrust, and even hatred of the ministry among many Indigenous leaders.

They remember the dreadful history of the residential schools program, and are determined never to repeat it.

Yet these are monumental responsibilities. Agencies that take on this duty are supposed to follow the same best-practice protocols as the ministry.

Recent audits reveal, however, troubling gaps in the level of care provided. Of six Indigenous agencies audited last year, none had a solid record of maintaining appropriate contact with the children in their care.

On average, the applicable standard was met only 41 per cent of the time, while one agency managed only a three per cent compliance rate. As well, a 2017 audit of the Nuu-Chah-Nulth agency found that this standard was met only one per cent of the time.

It was for this same failing that the ministry was so heavily criticized in the Chilliwack case. Of course, it’s to be expected that newly formed agencies will go through a learning experience. Several audits have shown problems with retaining qualified staff, or dealing with a widely dispersed population.

The onset of the COVID epidemic also made reaching children in care more difficult. Nevertheless, the dominating necessity in all child-care work is to ensure the safety of the child. With the ministry transferring so much of its workload to arm’s length agencies, the question becomes, how is this assurance to be given?

What’s needed is an effective system of self-reporting. Other public bodies, such as health authorities, regularly publicize outcomes, both good and bad. This transparency allows us to see whether they are providing decent or sub-standard care. A similar process is required for child-care agencies. The public and local communities are entitled to know what quality standards are in place and whether those standards are being met.

No doubt this is a daunting task. But whatever the cost, the safety of these vulnerable children must come first.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]