A commentary by a former journalist in Nanaimo.

Shootings, arsons, assaults, rampant public drug use, widespread theft, a profusion of urban tent encampments, daily overdoses that are too often fatal, a shocked mayor, and an overburdened public safety, health and security infrastructure.

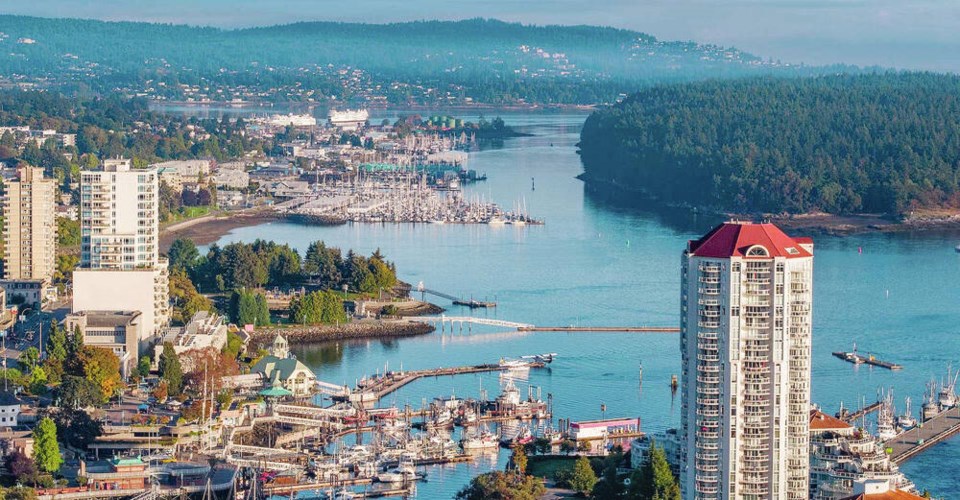

That describes the serious and seemingly intractable problems facing Nanaimo. But no one around the province should derive any satisfaction from thinking the Hub City is an exception in these matters.

Maybe 25 years ago that was possible, as the stereotype wrought by its blue-collar origins only began to diminish, but these are issues that now plague nearly every city in B.C.

From being a once-profitable processor of raw materials, Nanaimo has become a vital economic force in B.C. for tech, education, tourism, transport, research and more. But Nanaimo need not be defended. It can do that for itself quite nicely.

For many B.C. residents who go to work, pay their taxes, respect the law and care for their families, there is a looming sense of something going seriously wrong in our communities.

Citizens from Fort Nelson to Victoria are asking how to end the growing chaotic and criminal scenes described above and protect the civil society we sense to be at risk.

This crisis has been long in the making after various failed and failing economic and social theories were translated into federal and provincial government policy over several decades.

We all have our own biases about whom to blame, right or left, but it’s now time for something dramatically different.

The time has passed when we could expect action by government, police or social agencies to end this crisis. Besides, more of the same — poorly formulated policies, badly executed enforcement — we now know, will only worsen this already critical situation.

If we continue to turn to elected officials, bureaucrats, police and experts for solutions that they are unable to provide, then vigilantism is one real and growing risk, as we’ve seen. Vigilantism — mob rule — can only cascade into the chaos it claims to want to end. The vigilante inevitably becomes the next victim.

The novelist Leo Tolstoy, faced with similar social upheaval in 19th-century Russia, wrote an essay asking the question we in B.C. now want answered: “What then must we do?” The author of War and Peace can offer us guidance, not answers.

Tolstoy’s conclusion was that neither the do-gooders nor any amount of their charity money could solve the economic and social problems plaguing Russia in 1886.

In our case, no amount of housing, government programs, health reforms, increased policing or shifts in drug policy can or will end the mayhem on our streets.

Meaningful change, Tolstoy argued, arises only when the individual takes responsibility in a crisis for what they find possible, because wholesale change is unattainable. In other words, the catalyst for change lies in small but important actions by individuals. But, 137 years later, which actions?

To start, vote. Those who say that voting is useless are not only naïve and foolish, but aggravate current social problems by tearing at the fabric of civil society. Democracy works remarkably well when the majority of us think and participate. That’s how we achieved what we now want to protect.

Seek transparency and accountability from those in power. Events that created this crisis didn’t “just happen.” People in positions of power made wrong decisions without adequate scrutiny or sufficient accountability. As has been observed many times before, doubt can be a virtue.

These issues feel so big that most of us would rather leave them to others to solve. But without community support and guidance those others — mainly police and government officials — are as lost as we are and can come up with only partial and one-off solutions.

No single person, group, or ideology has the answer on how to end the urban encampments, the drugs, the crime and violence, the suffering; and nor should we trust those who say they do.

Ideas, thoughts, proposals, questions and suggestions that arise from individuals and filter upward are needed, not ill-considered solutions arbitrarily imposed as policy from above. Top-down solutions are usually unchecked, untested, idealistic and unfamiliar with the intricacies of the problems in question.

What then must we do? Participate in politics by at the very least voting. And we need to talk with each other, not curse, verbally or online, at who you think is your enemy. Insisting that one bromide is superior to the other is not political discourse.

Thoughtful and respectful conversations — at the kitchen table, the doughnut shop, or on a walk — filter outward and can influence our elected and bureaucratic decision makers. Such conversation also has the effect of creating connection with each other, which is much needed in times like this.

Just talk, think and listen; it need not be official, formal or guided. Let’s see what happens.

We might be surprised to see that small individual actions do translate into the solutions we all need and want.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]