Sept. 5, 2022, is the 100-year anniversary of a singular event in Victoria. On that day in 1922, Chinese-91原创 students in the city boycotted public schools, demanding equal rights to educational opportunities.

The boycott was a response to the growing Anglo pro-segregation pressures across the west coast of Canada in the 1920s, seeking a more complete separation of the Chinese and white races in public schools.

School segregation in Victoria, however, had begun well before that.

For two decades, pressure from some parents, and even from the Trade and Labour Council, had prompted the school board to segregate some Chinese students.

Using language as an excuse, the board stipulated that no Chinese children be admitted to public school without first “knowing and understanding the English language.”

And in 1908, although it was not required of any other immigrant group, a further ruling was introduced by the school board requiring Victoria-born Chinese children or the children of naturalized Chinese to pass an English examination before they would be permitted to attend public school.

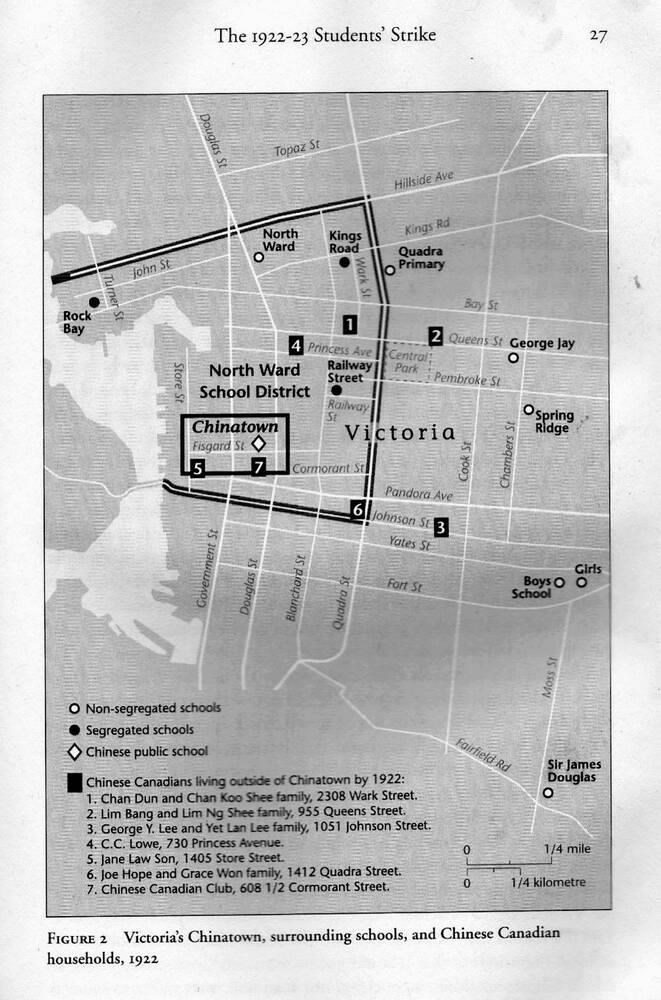

In November of that year, with the help of the chair of the school board trustees, George Jay, a policy was developed whereby all the Chinese students from grades 1 to 4 were segregated from public schools.

It is against this background that in 1922, the trustees voted to segregate all Chinese children from public schools to the end of Grade 7.

Given that, at the time, most children, including Chinese children, left school at age 14 to go to work, this policy effectively excluded Chinese children from daily interaction with other 91原创 children and deprived them of a crucial opportunity to learn the English language and Western customs.

Although Chinese parents had accepted the segregation to Grade 4 because they believed that it was better than having complete segregation, they recognized that segregation to the end of Grade 7 would be seriously detrimental to their children’s successful education in English.

The Chinese community believed that since they were taxpayers, their children were entitled to equality of educational opportunity, as they were here to stay and to become 91原创 citizens.

On Sept. 5, 1922, all the Chinese students were taken out of their schools and marched by their principals publicly all the way to the Chinese-only Kings Road School.

As they were walking towards the school, one of the senior boys suddenly gave a pre-arranged signal and the students quickly dispersed, leaving the principals alone on the route.

This remarkable protest by the Chinese in Victoria against the expansion of racial segregation in schools was the beginning of the anti-segregation movement in B.C.

The school protest lasted one year and halted the advance of school segregation. The school board returned to the pre-boycott segregation policy.

The protest brought the issues of the West into Victoria’s local struggle — it represented a stand against British Columbia’s anti-Asian movement.

The Chinese community stood up for what had to be done: They understood that if the Chinese permitted school segregation to be expanded, it would affect all future generations, not just of Chinese but all who were viewed as different.

The Victoria Chinatown Museum Society is commemorating this historical event with a walk following the route of those Chinese students who were called out of their schools in 1922.

We can only imagine the courage it took to defy those principals — courage not only of the children but of the whole Chinese community.

We must remember that in those days, laws controlled where the Chinese could live, what jobs they could take, and whom they could work for.

This courage would be sorely needed for the years ahead. The very next year, 1923, witnessed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which effectively denied any new Chinese admission to Canada.

The Chinese in Canada had to continuously negotiate their citizenship in their fight to be full-fledged citizens. It wasn’t until 1967, when Canada declared itself to be multicultural, that there was any real change.

It is important to acknowledge the Chinese community and the Chinese associations who organized the boycott for their foresight, their resistance and their resiliency.

Those of us of Chinese descent who came after were able to go to public schools as equals because our elders had the courage to act on their convictions.

It is one thing to know that injustice is happening; it is entirely a different thing to speak out and take action.

This 100th anniversary reminds us of our past, to commemorate the present and collectively take responsibility for our future so that this shameful history is never repeated for anyone.

For more information of the commemorative events go to: .

Grace Wong Sneddon is an adjunct assistant professor in Art History and Visual Studies at the University of Victoria and vice-chair of the Victoria Chinatown Museum Society.