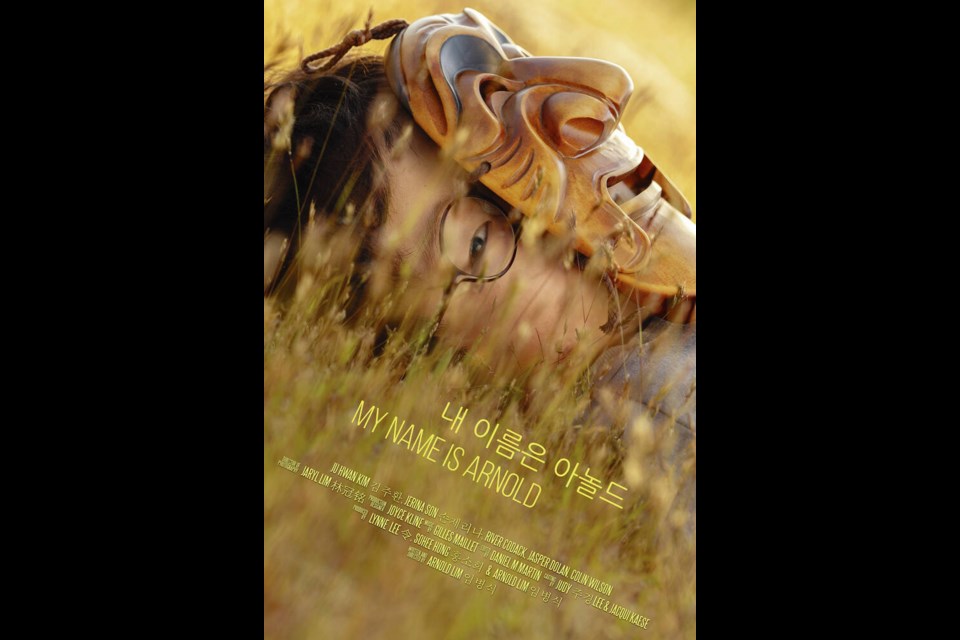

The film My Name is Arnold is screening at the Victoria Film Festival in February. It’s a short film about filmmaker Arnold Lim’s childhood experience growing up with immigrant Korean parents in a small rural B.C. town.

It shows the struggle of trying to fit in, and the bullying he received from his classmates due to his race.

I saw the film in November at the 91原创 Asian Film Festival.

Full disclosure, Lim is my friend and we’ve known each other for many years. I recall him talking about being bullied, but the film brought the experience to life, and gave me a different perspective.

Watching a little boy on screen be called racial slurs was hard. I forgot it was an actor and felt like I was actually seeing my friend on the screen fielding the abuse.

In a powerful scene, little Arnold justifies his actions of retaliation by saying they called me “C---k.” His mother responded that she gets called that, too, and ignores it.

The same week I saw the film, I had received some yearbooks from my family, and thought I’d thumb through them and enjoy the nostalgia of the experience.

I picked up the package, put it in my car and headed home. On the drive home, I told my daughter that I had yearbooks from the 1990s. Eagerly, she opened the books and started flipping pages as I drove.

She stopped, and looked at me, concerned.

“Did your enemies sign your book?” she asked.

My first thought was that the word enemies seemed out of place. I never had any “enemies.”

When I looked down at the pages in my yearbook, I was a little shocked at the words. I read them, then answered my daughter: “Those were from my close friends.”

Many of the comments were racist and referenced me being Indigenous.

Some of the comments included “What’s up Indian,” “Hey Prairie N-Word,” and “Keep on drinking the Lysol.”

Even acknowledging it was a different time, it was never OK. There are no excuses.

I am not in touch with my former classmates, I moved away at 18. I feel in my heart that the classmates who signed my books have gained understanding and wisdom and wouldn’t speak like that today.

I don’t write this to shame them — it was more about me reflecting on what was “normal” in my teens, and the fact that I accepted that behaviour.

It makes me upset with myself that I didn’t stand up for myself, or have better standards when choosing friends, or at least correcting behaviour.

When I was 14, I was walking with my friend from school when we passed a group of Indigenous teen boys in an alley. “Hey, white boy, come tie my shoes,” they yelled.

They kept demanding my friend tie their shoes, and we kept walking.

Then the Indigenous boys looked at me and said: “What are you doing hanging out with that white boy?”

I don’t recall how I responded.

Later, my friend told me how angry he was, and that they were out of line. I tried to tell him they were probably just trying to be funny.

He said it wasn’t funny. I agreed it wasn’t funny and then asked what he thought about the names that he and the rest of our friend group called me.

“Oh, I didn’t realize,” he said.

Every yearbook from middle and high school had similar comments.

I remember being called those names by friends and I remember trying not to care.

My yearbooks didn’t age well, but they serve as a reminder of what was considered acceptable.

It made me sad when I saw my daughter’s disappointed face, thinking only bullies and enemies would write those words. It made me feel like I let her down, for accepting it when I was her age.

Watching Lim’s film almost gave me a sense of camaraderie that it wasn’t just me. Sadly, for people in my generation, these stories are more common than we would like.

The fact that our children are horrified by the overt racism from the past shows we’re getting somewhere.