A Parksville equestrian instructor whose cancer metastasized while she was waiting for chemotherapy worries late-stage patients like herself are being sidelined in an overwhelmed cancer-care system, especially on the Island.

Loni Atwood, 43, whose rare adrenal cancer was discovered during an emergency-room visit in April 2022, says that after surgery, she was twice advised to wait for preventive chemotherapy because of the supposed low risk of spread and high volume of cancer patients needing treatment.

“They rolled the dice with me,” said Atwood. “I think when you know you’ve got proven aggressive cancers, I don’t think that’s the right management strategy.”

In February of this year, while at the ER for a colonoscopy, Atwood learned the follow-up scan results on her file showed her lungs were littered with tumours, so much so that chemotherapy may be ineffective.

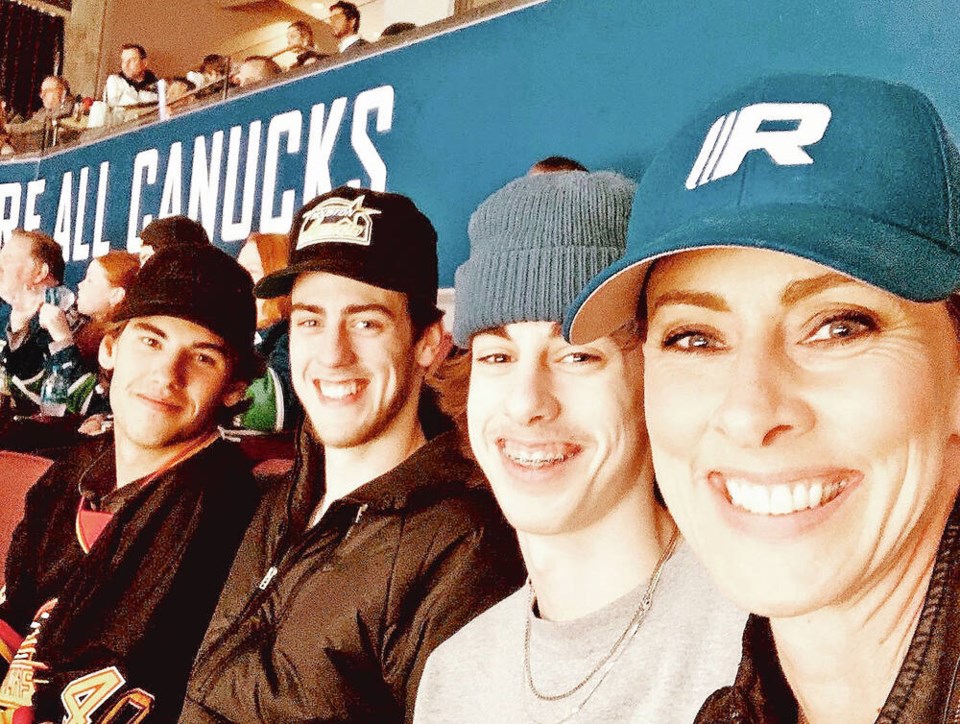

Atwood, a single self-employed mother of two teenage sons, Brandon, 19 and Garrett, 16, said she was heartbroken. “I thought: ‘There’s no way I’m leaving my kids, like this isn’t happening.’ It was too awful to be true.”

She said she trusted the system. “I felt like a number and that they were giving up on me.”

Atwood is one of a number of Island patients telling their stories in recent weeks of cancer-treatment waits that prompted them to head to the U.S. for treatment, or, in the case of one man, choose medical assistance in dying after an unbearable wait for chemotherapy for Stage 4 esophageal cancer.

Premier David Eby, at an unrelated news conference this week, called the stories “horrific”and said any wait times for cancer treatment are “unacceptable” for the patient, their families and for him.

Eby directed B.C. Heath Minister Adrian Dix and the B.C. Cancer agency to further address the problem.

Concern over radiation-therapy wait times spurred the province to offer eligible breast and prostate cancer patients waiting for radiation therapy the option of receiving treatment in Bellingham, Washington, all expenses paid.

“We want to reassure all B.C.ers we’re bringing every available resource to address their need to get this service within the clinical guidelines so that they can rest easy in what must be an incredibly difficult time,” said Eby.

Atwood’s adrenal cortical growth was removed on May 20, 2022 at 91ԭ�� General Hospital. A pathology report came back in September, followed by a diagnosis of a rare type of adrenal gland cancer called adrenocortical carcinoma in November 2022.

Atwood says she was advised to delay IV chemotherapy until the results of the next scan. Those scan results, which she only received in February 2023 as a result of a visit to the hospital for a colonoscopy, showed the cancer had riddled her lungs and spread to her blood.

It was another two months, in April — a full year after she first went to the ER — that she met with a B.C. oncologist who said it was doubtful, based on the spread, that chemotherapy would yield the desired results. Nevertheless, she was started on chemo in May.

Dr. Kim Nguyen Chi, head of B.C. Cancer, said in a phone interview this week that human resources is the biggest challenge in the face of cases increasing at a rate of about three to five per cent a year. “We need to catch up,” he said.

The agency is also tracking whether there was an increase in late-stage cancers being diagnosed post-pandemic, he said.

While the goal is for everyone diagnosed with cancer to see an oncologist within four weeks of referral to B.C. Cancer, given the shortage of oncologists, patients “unfortunately” have to be prioritized by need at times, said Chi.

“People are prioritized and re-prioritized but it’s not something we want to do.”

A massive hiring effort is helping the system to meet the four-week benchmark, he said. About 27 radiation therapists and 61 oncologists — including radiation and medical oncologists as well as GPs trained in oncology and nurse practitioners who support oncology patients — have been hired, including about 10 oncologists on 91ԭ�� Island, Chi said.

“Victoria has had a tremendous growth in oncologists,” said Chi, who says while it’s “phenomenal” that B.C. was able to recruit 61 oncologists so quickly, “more than that” are needed.

The impact of the new hires will become more apparent in the coming months, he said.

Chi said wait times for chemotherapy in Victoria are currently close to the benchmark, which is to have 90 per cent of people treated within two weeks of referral for chemotherapy. Wait times for chemotherapy are not public.

The large majority of people in Victoria are getting their chemotherapy within two weeks, said Chi. Because chemotherapy is often a final step in treatment — maybe following weeks and months of diagnostic tests, surgery and imaging — it can in some cases seem longer than benchmarks.

“The perception of the wait time may not necessarily be related to the actual getting the chemotherapy treatment, but it’s the totality of the wait time that they’re experiencing, which is an entire system problem, which of course needs to be fixed as well,” he said.

Chi said people with late-stage cancers deserve “the highest quality care as possible.”

“I am sorry that there is a perception that people are feeling sidelined because we certainly don’t want that to happen,” he said. “For the patients that are in the system, the vast majority are receiving their treatment on time, on schedule, as clinically needed and are getting great care.”

And while there are gaps in care, Chi said all parties involved are putting in tremendous effort to improve the system and are closing these gaps. “I think we will see change in this coming year,” he said

As for Atwood, her six sessions of chemotherapy ended in October, and she says the cancer has been contained and tumours have decreased.

She is privately paying for hyperthermia treatment, a method of heating body tissue to help kill cancer cells, via a naturopath and meanwhile continues to ride horses and teach.

“It’s really stressful because I’m supposed to be resting and balancing but I have to earn, I don’t know how else to do this,” she said.

Atwood will remain on the chemotherapy pill Mitotane, which includes side effects from nauseau to neuropathy, for the next 18 months in order to prolong her life. She’s been declined funding for an expensive drug via a phase 2 clinical trial.

“After that, there is no plan from B.C. Cancer — that’s it, that’s the end of the road for me,” said Atwood.

“There has to be something better than that. That’s why I’m not taking my foot off the gas.”