Critical shortages in every branch of the health-care sector have critics wondering when the promised new medical school at Simon Fraser University will break ground.

But one emergency room doctor called for more immediate action, saying those without a family doctor can’t afford to wait the years it will take to train a new generation of physicians.

The B.C. Liberals are calling on the NDP government to fulfil its “broken promise” of creating a second medical school in B.C., at Simon Fraser University, and increasing the number of seats at the University of British Columbia’s medical school from 288 to 400.

“This is a government that promised a second medical school at SFU Surrey and we have had zero indication that they intend to follow up on it,” said Shirley Bond, the B.C. Liberal health critic.

Premier John Horgan promised during the 2020 election campaign that if re-elected, the New Democrats would fund a new medical school at SFU. The two budgets since the election have not included construction funding.

The Opposition also wants the province to make it easier for internationally trained doctors to practise here and to increase the residencies available for international medical graduates from 56 a year to 150.

In April, the province announced a plan to fast-track accreditation for internationally trained nurses to address the staffing shortage, but no such plan was announced for doctors who studied abroad.

Health Minister Adrian Dix said Tuesday that he’s been calling for a new medical school since 2011, when he was leader of the opposition, an idea that was not supported by the ruling B.C. Liberals.

SFU is developing a business case for the new medical school, Dix said, so there is no firm date on when it will break ground.

“This is something that is important and significant over time, but not really as much related to the present crisis,” Dix said, noting that it takes years to build a medical school and produce medical graduates.

“We’re seeing challenges — particularly in family practice medicine, but in all medicine — now. We’re going to see more challenges within 10 years,” said Dix, given the population of people over 75 is set to double in the next decade.

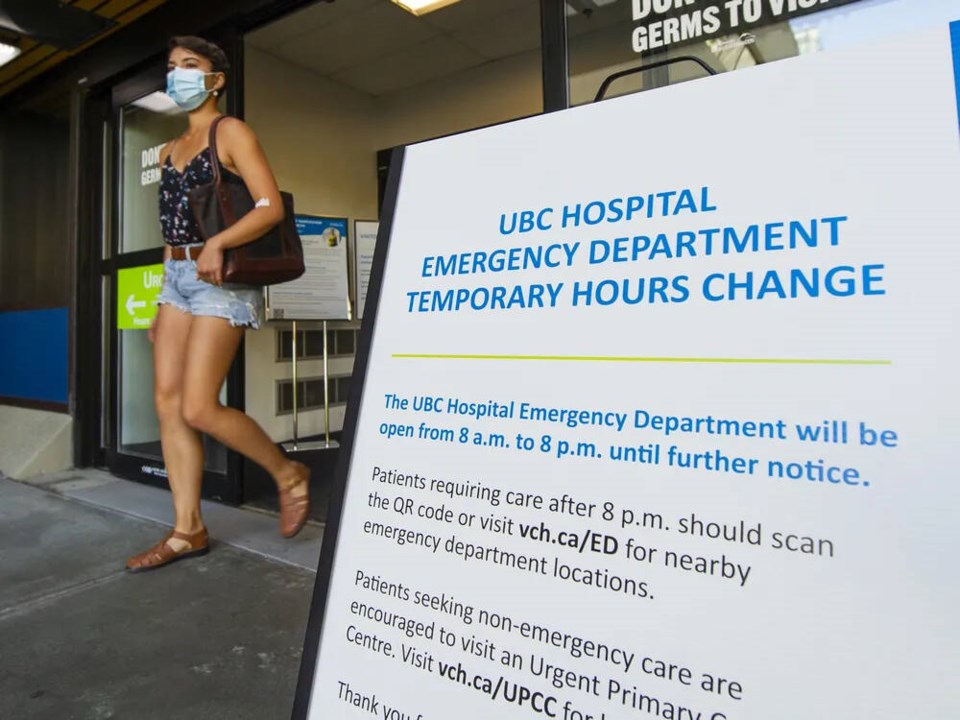

The staffing crunch has led 91įŁ┤┤’s UBC Hospital emergency department to scale back its hours. Effective Tuesday, the emergency department will admit patients from 8 a.m. until 8 p.m. rather than to 10 p.m., 91įŁ┤┤ Coastal Health announced Monday.

The health authority said this will allow emergency physician coverage across acute care sites in 91įŁ┤┤ while also ensuring staff and physicians are not constantly working overtime, which is causing burnout.

People who need emergency care after 8 p.m. can go to 91įŁ┤┤ General Hospital, St. Paul’s Hospital, or, for children and youth, B.C. Children’s Hospital.

“Increasing patient arrival volumes, especially at the end of the day, has meant that staff and medical staff at UBC Hospital ED are routinely working well beyond their scheduled shifts into the early hours of the morning to deliver care to those who arrive at the hospital in the late evening,” Dr. Ladan Sadrehashemi, VCH’s senior medical director for 91įŁ┤┤ acute care said in a statement.

“The uncertainty of not knowing the last shift end time is creating burnout and loss of medical and other staff … and is not sustainable.”

Dr. Michael Curry, an emergency room physician at Delta Hospital and clinical assistant professor with the University of British Columbia, said it’s unfortunate UBC Hospital is scaling back hours since any reduction in emergency room capacity puts patients at risk.

“I can think of one personal case where somebody had a life-threatening injury within a couple 100 metres of UBC Hospital,” he said. “They very well could have died if they had to be transported to 91įŁ┤┤ General Hospital.”

The crisis in primary care — with one million British Columbians without a family doctor — is putting pressure on short-staffed emergency rooms which are getting more patients who haven’t had adequate preventive care, Curry said.

For example, he said, emergency room doctors are more often seeing patients with delayed diagnoses, people coming in to have their prescription renewed or patients coming in with chronic problems that have been persisting for years.

“The only entrance into the health-care system for an increasing number of British Columbians is through the emergency department,” he said, which adds to patient frustration and staff burnout.

91įŁ┤┤ Coastal Health is reviewing a July incident in which a woman died after spending two days on a stretcher in an overcrowded and understaffed North 91įŁ┤┤ hospital waiting room.

While he supports more training seats to educate the next generation of doctors, Curry said even if the new medical school at SFU opened tomorrow, it would be six to 12 years before those doctors are practising.

That shows a “lack of foresight” in shoring up a “health-care system that’s been running on fumes for years,” he said.

Short staffing has caused some small town emergency rooms, including those in Port McNeill and Port Hardy, to close temporarily. That creates a backlog for paramedics who must transport a patient to the closest hospital with an open ER.

With about a quarter of the 2,400 paramedic jobs vacant, there aren’t enough paramedics to staff backup ambulances in small communities.

That was the case on Sunday in Ashcroft when a man in his 80s went into cardiac arrest. The man was within 200 metres of the ambulance station but had to wait 28 minutes until paramedics arrived.

“When you call 911 in British Columbia, you should expect an ambulance to respond,” Bond said. “While it is absolutely devastating for Ashcroft we are hearing similar stories of a health care system in crisis all across our province.”