ALGIERS, Algeria - The awe-inspiring dunes and wild mountains of Algeria's Sahara have lured adventure travellers for decades, but their latest incarnation ŌĆö as a crossroad for the al-Qaida militants who attacked a natural gas complex ŌĆö is likely to make them even more inaccessible.

At least 37 hostages died in the four-day siege deep in the desert. Algeria's government, ambivalent about tourism in the best of time, is expected to impose new restrictions on the vast south, whose residents eke out a living on the few intrepid tourists who arrive.

"The Sahara is an iconic wilderness much like the Himalaya or Antarctica and most agree that Algeria, the ninth biggest country in the world, is the best place to experience the full range of desert landscapes, authentic Tuareg culture, pre-historic rock art, adventure and so on," said Chris Scott, a Sahara guide and author. "It's all there and the people of the south have decades of experience in delivering what tourists want."

Scott just returned from leading a two-week New Year's camel trek through Tassili N'Ajjer National Park, 400 kilometres (250 miles) south of the Ain Amenas gas facility that was attacked.

But he is an exception. The numbers of tourists visiting the deep south dropped from 1,807 in 2011 to 643 last year, according to authorities in Tamanrasset, the main Saharan city. Already, 70 of the 76 tourist companies in the city have closed, and most Europeans planning on coming cancelled their reservations after the attack, said Azzi Addi Ahmed, head of the local tourism association.

This is a far cry from 20,000 tourists a year in the 1980s, when restrictions were few and you could travel without the local tourist agencies that are now mandatory.

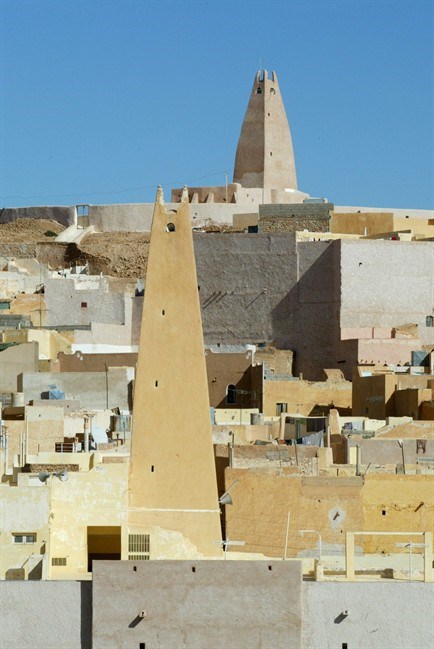

The region has long been loved by Europeans. The towering dunes and palm-fringed oases that epitomize the desert can be found in Algeria's Grand Ergs. Even farther the south, the rugged wind-carved mountains are dotted with 10,000-year-old cave paintings.

In 1911, a French soldier turned monk made his home among the Tuareg tribesmen and built a hermitage atop the nearly 10,000 foot (2,800 metre) Mount Assekrem in the Hoggar range near Tamanrasset, describing the surrounding peaks as more magnificent than any cathedral.

"My hermitage here is on a summit that overlooks practically the whole of the Hoggar and stands amid wild-looking mountains beyond which the seemingly limitless horizon makes one think of the infinitude of God," wrote Charles Foucauld.

Even then, the southern deserts were perilous: He was killed by marauding Senoussi tribesmen in 1916, and beatified by the Roman Catholic church in 2005.

The Sahara was largely closed to tourists during Algeria's years of civil war and wasn't reopened until the late 1990s when business rapidly picked up as Europeans rushed back to do desert safaris.

But, the government's victories against the militant Islamists in the north forced them to find refuge in the deserts to the south, mainly in northern Mali and Niger, where they engaged in smuggling and then the occasional lucrative kidnapping of foreigners.

Algeria's desert tourism received a major blow in 2003 when a precursor to al-Qaida snatched 32 foreign tourists, though all but one were eventually rescued and business recovered.

All that changed, however, when the overthrow of the Libyan regime flooded the desert with weapons, and a rebellion broke out in neighbouring Mali, massively boosting al-Qaida's strength in the region.

"Already a large number of agencies have closed, leaving just those who do it for the love of the business to barely scratch by," said Iyad Gholami of the Assouf desert travel company in Tamanrasset. "We're collateral damage from the security crisis."

Phil Hassrick, who runs the California-based Lost Frontiers adventure travel company, stopped going to Algeria a few years ago.

"We couldn't guarantee the safety of the clients," he said, though back then it was more concern with banditry.

The impact is the most severe on the local Tuareg for whom tourism was one of the few sources of income, aside from smuggling.

Over the past year, the government said it would try to encourage Algerians to travel to the south, including periodic government and company visits, but operators complain that the visits are short, rare and don't involve the weeks of driving or trekking through the mountains desired by foreigners, who paid $1,500 a week to local guides.

In December, the remaining agencies petitioned the government to save the industry.

"At the very least we ask for the erasing of the debts linked to accumulated taxes as has been done for other sectors in difficulty, such as agriculture," Ahmed suggested. Lowering fares to the south on the state-owned carrier, Air Algerie, would be a big help, he said, but fears it may be too late.

"The attack on Ain Amenas is for us the coup de grace," Ahmed said. "It is the death of tourism in south Algeria."

_______

Schemm reported from Rabat, Morocco.