TORONTO - Leading influenza scientists have ended a self-imposed moratorium on research into what it might take to make bird flu viruses transmissible among humans.

The international group announced their intention to resume work in the controversial field in a letter published jointly by the journals Nature and Science on Wednesday.

The letter acknowledges that work cannot immediately resume for U.S.-based or U.S.-funded researchers, because the Department of Health and Human Services is still finalizing a framework for how such work will be approved in future. That process is described as being a few weeks from completion.

The decision brings to a close a moratorium that was meant to last two months, but instead stretched on for just over a year.

"It's a long 60 days," said Ron Fouchier, a Dutch virologist whose laboratory at Erasmus Medical Centre in Rotterdam is a world leader in this work.

The scientists said that because of the risks posed by the H5N1 flu virus, they have a public health responsibility to resume this research. But others expressed concern over the move, suggesting it was premature.

And a leading scientist who has argued that this work should not be undertaken at all called the lifting of the moratorium "outrageous."

"I think it's just a snow job," Richard Roberts, a 1993 Nobel prize winner for medicine, said when asked whether his concerns had been assuaged by the various international meetings that have taken place over the last year and the protocols that have been developed in that time.

David Relman is a member of a U.S. advisory panel that first raised red flags about this work. He remains unconvinced that its benefits outweigh the risks of creating an H5N1 virus potentially capable of easily infecting people.

"I buy the argument that this can happen — at least biologically — in the laboratory and hence it may happen in nature," said Relman, a microbiologist who teaches at Stanford University in California.

"But as to what it will look like and how to be pre-positioned to detect that specific thing? I think this only advances our abilities there in a very narrow, limited way."

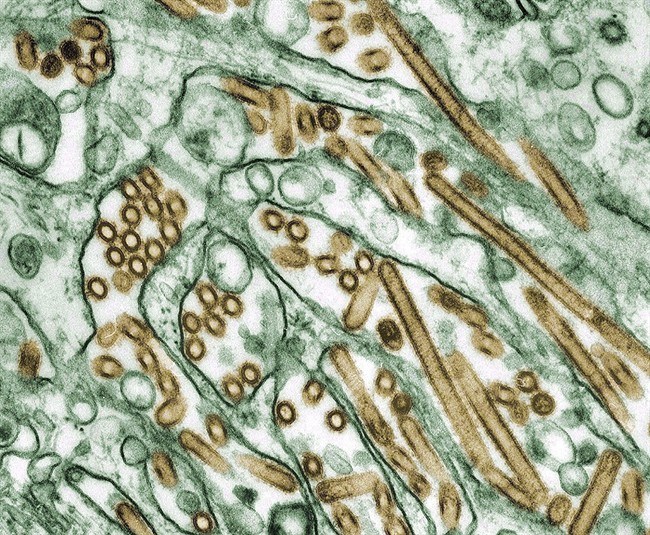

The moratorium was offered as a good-faith gesture last January, when the flu community was embroiled in a controversy over two studies that showed how H5N1 viruses could evolve so they could spread between ferrets, in the way regular flu spreads among humans.

(In influenza research, ferrets are a common stand-in for humans, because the disease acts in them much as it does in people.)

Fouchier's lab produced one of the studies. The second was performed by a group led by Yoshihiro Kawaoka of the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the University of Tokyo.

Two months earlier the U.S. National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity — the panel on which Relman sits — urged the U.S. government to try to block publication of the two studies. Sharing details of how to engineer a bird flu virus that can spread easily among mammals posed a grave biosecurity risk, it insisted.

Science and Nature, which published the research, refused to redact key details and the studies were eventually published in full last year.

Michael Osterholm, an NSABB member who also opposed full publication of the studies, said he believes highly skilled labs like Fouchier's and Kawaoka's should pursue this line of study. However, he fears laboratories with less stringent procedures might try to repeat the work in less secure settings.

"If this now just starts resulting in papers getting published with very detailed methodologies for how to make mammalian transmissible H5N1 (viruses), it really does open up the possibilities for laboratories that would not otherwise have had the ability to do so to make these viruses," said Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Diseases Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota.

The World Health Organization's point person for the issue, Dr. Keiji Fukuda, said it is reasonable at this point to lift the moratorium, though he noted there are still issues to be worked out about how to handle biomedical research that triggers so-called dual-use concerns.

Dual-use research is science that is undertaken for legitimate reasons, but which could be used with malicious intent.

Fukuda said the WHO will be hosting a meeting on the dual-use issue in late February.

The moratorium covered only H5N1 studies that relate to what is called gain of function — changing the virus to enhance its transmissibility or lethality or to add to the number of species it can infect.

Currently the H5N1 virus occasionally infects people, but does not spread among them as human flu strains do. Over the last nine years, 610 confirmed H5N1 cases have been reported in 15 countries and 360 of those people have died.

Scientists had been trying to figure out whether the virus could evolve to easily infect people. They argue knowing the mutations needed for person-to-person spread will arm laboratories that monitor the strains circulating in nature, so they can spot viruses that might be making the transition.

The controversial studies showed as few as between five and nine mutations may be all that is needed to give the viruses the ability to transmit from ferret to ferret through airborne droplets, the way flu viruses can spread among people. Some H5N1 viruses already have a couple of those changes.

Kawaoka warned that for flu viruses, this is not an insurmountable obstacle.

"Nine mutations for influenza viruses is almost none, it's so easily mutated," he said. "The risk exists in nature already. And not doing the research is really putting us in danger."

Kawaoka is one of the researchers who must still wait for the U.S. government's go-ahead. Fouchier has U.S. funding, but his work is supported by the European Union as well. So he is already taking steps to get his laboratory back into action.

He wants to figure out what the minimum number of changes needed is, and to see whether the mutations required to make viruses transmissible are standard for all H5N1 virus types, or whether viruses from Indonesia and Egypt, for example, require different changes.

"I've been convinced from the beginning that this work can be done safely and is done safely by the laboratories who are doing it," Fouchier said. "And therefore they should continue this work and hopefully prevent future pandemics — and certainly with H5N1.''

Roberts does not agree that this work must be done to protect against a H5N1 pandemic. He said there is no way to guarantee that the results found in the artificial conditions of a laboratory will predict what will happen in the wild.

He suggested the issue has mainly been debated and decided by members of the flu research community, with few outside voices heard. Researchers who oppose this work are afraid to speak up for fear their funding from the U.S. National Institutes of Health might be threatened, he said.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the NIH's National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases, insisted, though, that the issue has had a full airing, with multiple international meetings involving biosecurity experts, lab safety experts and others.

"So I don't think people can say the effort was not put into trying to discuss this in an open and transparent way," he said.