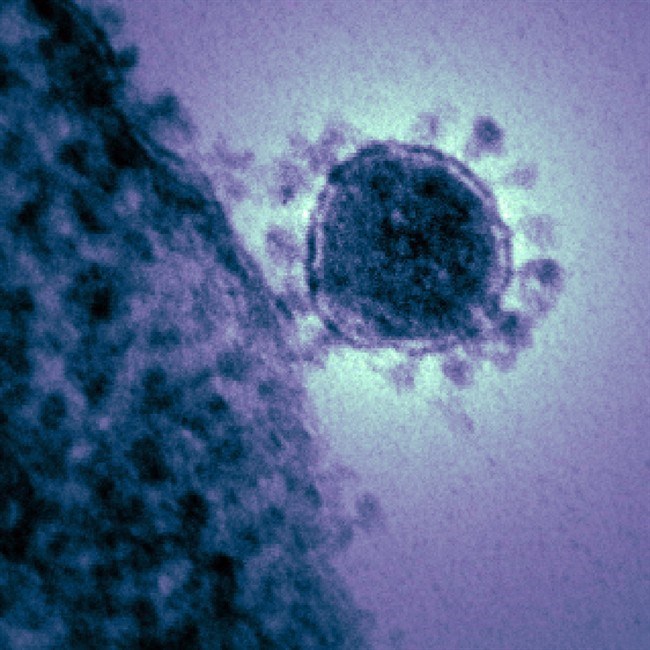

TORONTO - Viruses closely related to the new coronavirus that emerged last year in the Middle East have been discovered in specimens from a number of species of bats found widely throughout Europe and beyond, a new study shows.

The work suggests bats common to Europe, Russia, parts of Asia and Africa and the Middle East may carry viruses that are very closely related to the new coronavirus, called EMC 2012.

The study will be published in the March issue of the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The findings, while interesting, don't help to narrow down how a dozen or more people in three countries have been sickened by the new virus, or whether more have been infected but have escaped notice because their symptoms were mild.

The researchers said bats from the Arabian Peninsula should be tested to see if they carry similar viruses. But senior author Dr. Christian Drosten cautioned that because of the wide geographic distribution of these bats, it cannot be concluded that the bat virus that evolved into the new coronavirus did so in the Middle East.

"It could have come up in any other region where those bats are prevalent," said Drosten, a coronavirus expert and director of the Institute of Virology at the University of Bonn Medical Centre in Germany.

While it is believed the new virus came from bats, it's not known whether it moved directly from bats to people — through exposure to bat guano or urine, for instance — or whether some other animal or animals such as some form of livestock became infected and passed the virus on.

The SARS coronavirus, a cousin of EMC 2012, evolved from a bat virus that made its way into wild animals — civet cats and raccoon dogs — that are eaten as delicacies in China. "We don't know (yet) what the raccoon dog is for this virus, but there may be one," Drosten said.

He and colleagues had done previous research on bats in Ghana and in four countries in Europe — the Netherlands, Romania, Germany and Ukraine. As a result of that earlier work, they had stored fecal samples from nearly 5,000 bats. After EMC 2012 emerged, they tested the samples looking for coronaviruses.

They found previously unknown viruses related to the new coronavirus in nearly 25 per cent of Nycteris bats, and 15 per cent of Pipistrellus bats. The viruses from the latter were most closely related to EMC 2012. In one case, the genetic codes differed by less than two per cent.

Three of four Pipistrellus bat species tested positive for the similar coronaviruses, Drosten said. "The whole Old World region is full of different Pipistrellus species. And I wouldn't be surprised if all of them contain related viruses."

So if these bats commonly carry viruses similar to the new coronavirus and carry them throughout many parts of the world, why have infections only been seen in Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Jordan? And why now?

Do the cases — nine confirmed plus a similar number of probable cases — represent multiple introductions of virus from bats to people, like sparks from a fire? Or did the virus jump once and spread, mostly unseen, from person to person?

At present, those questions have no answers. But there are ways to find clues, particularly to the question of whether the virus made multiple jumps from its bat reservoir.

Generating genetic sequences from all the viruses that have infected humans — where virus has been isolated or virus fragments are available — would give scientists information to compare.

Each type of virus evolves at a particular rate. The speed is referred to as its molecular clock. Comparing genetic sequences from the first known cases to later cases should show if the human viruses have evolved from one another.

The first spotted case was a man from Jeddah, Saudi Arabia who died in June. But in November, a Cairo-based U.S. naval research laboratory confirmed that two people who died in Jordan in April 2012 had been infected with the new virus.

"We will never have a definite answer unless we find the source. But we will have very, very clear hints if we sequence more viruses," Drosten said. "The further apart in time, and in geography, those virus sequences are, the more we will learn."