One hundred and fifty years ago, the Daily British 91原创 marvelled at a new shipyard with first-class facilities for repair and construction of large ships, calling it an example of what “energy and perseverance can accomplish.”

Collings & Cook’s Ways, which opened for business in 1873, was one of the first shipyards in the province. Called Point Hope since 1938, it’s the last surviving shipyard in a harbour that once housed a thriving maritime industry.

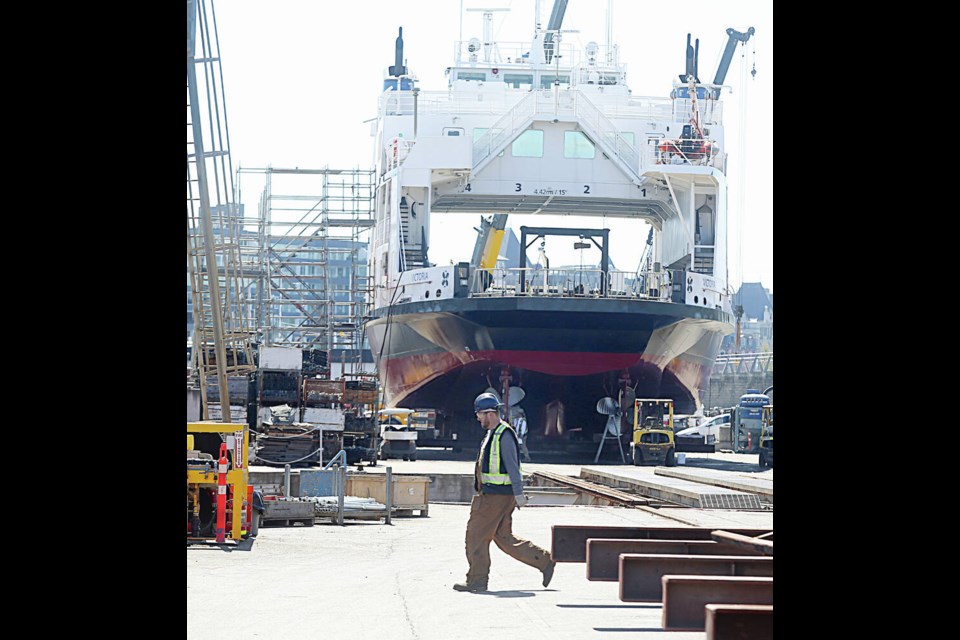

Sitting on nine acres of land and five acres of water lots along Victoria’s Upper Harbour, it has established a reputation for its work in repair, refit and maintenance on vessels from 60 to 160 feet.

And despite an ongoing labour shortage, development pressure all around it and an inflationary environment that puts the squeeze on costs and taxes, it remains the beating heart of Victoria’s industrial lands and a constant reminder of the city’s history.

These days, business is brisk, with steady work for as many as 200 workers on any given day and contracts with 600 local firms for supplies and services.

But Riccardo Regosa, Point Hope Maritime’s general manager, said the fact the shipyard is still around is a feat in and of itself.

“When the Ralmax Group bought the shipyard out of bankruptcy in 2003, this business was gone — there were eight employees left and the shipyard facilities were worn out,” he said, adding the day the company signed the lease with the city, Transport Canada condemned the docks.

Regosa, who joined Point Hope in 2016 after 17 years working for Damen shipyards — the company that builds B.C. Ferries vessels — said Point Hope may only be 20 years removed from bankruptcy, but it’s nothing like the old operation.

Building on the foundation established by previous general manager Hank Bekkering, who Ralmax founder Ian Maxwell hired to rebuild the shipyard in 2006, the shipyard is “thriving,” he said.

Shortly after buying the assets, Maxwell shut down the yard, and spent more than $20 million to modernize the facility, introduce new environmental systems, a new pier and a marine railway, turntable and spur lines that allowed the yard to work on multiple vessels at a time.

Maxwell would later buy the property in 2014 and begin another round of investment to extend the spurline, build new workshops and modernize equipment.

Dry berths were increased to drydock up to six vessels at one time. “We tripled the number of drydockings we do each year and the same applies for the number of employees,” said Regosa. “And we made achieving the highest industry standards for health and safety and environmental systems management priorities.”

The shipyard now counts among its clients the Royal 91原创 Navy, 91原创 Coast Guard, B.C. Ferries and area tug and fishing vessels.

Since 2017, Point Hope has been the choice drydock facility for all of B.C. Ferries’ smaller vessels. Two years later, Ralmax purchased the Esquimalt Drydock Company, giving it a foothold at the federally owned Esquimalt Graving Dock, which allows them to work on the entire B.C. Ferries fleet.

Maxwell said the company understands the shipyard’s place in history as well as its role in creating a healthy, diversified local economy.

“We are learning from the history of Point Hope and embracing our own business model to avoid the boom and bust cycle that is largely created when owners hive off profits to benefit a few at the top rather than reinvesting profits in infrastructure, and in people,” he said.

‘It wasn’t rocket science’

What Maxwell, who has been vocal about the need to protect what little industrial land remains in the city, saw in the bankrupt shipyard in 2003 was a solid business that had lost its way.

He recalls combing through the books with his accountant and determining that if the “shipyard stuck to its knitting,” it would do well in the ship-repair business.

“They actually had quite a nice business that was doing about $5 million to $7 million a year in revenue. But it needed investment, it needed the flexibility to bring in more than one vessel in at a time,” he said.

“It wasn’t rocket science. I just listened to other people, the people who were working there and knew what it needed.

“The reality is business isn’t looking into the crystal ball and doing absolutely amazing things. Business is doing the same logical thing over and over lots of times. Every year, make a little bit of money, give your people some raises and take the balance of the money and put it into new equipment and then shampoo, rinse, repeat.”

The biggest feat may not have been resurrecting a business, but preserving the land.

Maxwell sees himself as a steward of the industrial site, which provides the kind of work that allows employees to establish families and set down roots. He sees his harbour holdings as something to be maintained long after he’s decided to put up his feet.

“If you looked at it as an asset, you’d believe all that s**t that B.C. Assessment says about what you could sell the land for,” said Maxwell, referring to one of his biggest headaches — B.C. Assessment valued the shipyard at $38 million this year, an $8 million increase over last year, resulting in a massive increase in his taxes.

“I see it as this is where the people that I care about, the people that I actually like and admire, this is where they all work. This is where apprentices are going to say: ‘I served my apprenticeship at Point Hope and United Engineering and I worked on that bridge that came from China and we fixed it at Point Hope.’ “

Bryan Salema, a 37-year-old project manager at Point Hope who started as a labourer 15 years ago, remembers feeling awed by the fact Point Hope was one of the first shipyards in the province and that he was part of a long tradition and the history of the city. “I took a lot of pride in working here,” he said.

He said he and other workers have been given opportunities to take on new positions and responsibility. “Every opportunity I asked for I was given a chance. If you persevere and show the willingness to be here, there’s apprenticeship programs for almost every trade — the opportunities are there for you,” he said.

Jennifer Henry, a labourer who has been at the shipyard for three years, said she found another family at Point Hope, one that’s been helping her learn the tools and tricks on the site as well as job training.

“The guys at work are very supportive,” said the 32-year-old member of the Pauquachin First Nation.

Henry said the shipyard has made big strides in ensuring women in trades are more comfortable, which has translated into more women working on the site over the last few years.

She said she’s had the opportunity to try her hand at a number of positions as she figures out what trade she would like to focus on.

“I have a few people that I became very close to and they’ve been my rock in the shipyard, because it’s all new to me. There’s been challenges in the yard that just were a little overwhelming, but those people just had my back and I was able to work through it.”

The need for a graving dock

While getting the shipyard humming is one thing, ensuring Point Hope is around for another 150 years may be may be more tricky.

The shipyard has plans to establish a graving dock that will allow it to service vessels up to 560 feet in length, meaning it could handle most Royal 91原创 Navy, 91原创 Coast Guard and B.C. Ferries vessels.

But first, it needs to secure years’ worth of future work, Maxwell said.

That would allow the company to invest heavily — a graving dock has been estimated to cost in excess of $100 million — and to attract and train a workforce, which Maxwell says is likely a five- to seven-year process.

“If we don’t have a steady supply of work, then we have our workforce going up and down. If we can’t put together that quality workforce, then we can’t say: ‘You can rely on us.’ ”

Regosa said if Point Hope can rely on a predictable body of work from clients like B.C. Ferries, the 91原创 Coast Guard and Royal 91原创 Navy, which are renewing their fleets, the graving doc project can go ahead.

“We all have seen the impact that the National Shipbuilding Strategy had on the selected shipyards throughout Canada, a predictable income stream of, in this specific case, billions of dollars for decades to come that allows them to commit to large investments in their infrastructure.

“It is a logical and viable option that we continue to hope governments will consider.”

Without the graving dock, the shipyard faces challenges, as the new larger vessels at B.C. Ferries and other clients will not fit in the existing facility. “Fleet owners are not shrinking their capacity — they are increasing capacity by replacing the old vessels with larger new ones,” said Regosa.

Maxwell notes the shipyard also still has to contend with politicians who don’t understand its economic impact and the importance of maintaining industrial land in the city.

While the ship-repair business is booked solid, it still feels pressure from developers who see the site as ideal waterfront space for mixed-use and residential projects, from new residents in the area concerned about noise, and from politicians who often see commercial and industrial land as a chance to cash in.

This year, Point Hope was hit with a 37 per cent increase in its taxes, the only industrial site in the city to face that kind of hike.

Maxwell said what cost him $540,000 in property tax in 2018 will now cost him $1.6 million. “Does that seem like they’re trying to tell us they understand what we do or value what we do?”

He noted that the amount of industrial land paying property tax in the city is down to one per cent — “because they’ve forced all the industrial lands out of here.”

The tax hit means Point Hope and Ralmax may have to cut back on reinvesting in equipment and facilities, a feature that had given the company a competitive edge for years.

Maxwell said politicians have been telling him since 1995 that they want to make the taxation regime more equitable for industry. “There’s been umpteen mayors between then and now. Every one of them has sung the same song,” he said. “And yet nothing’s changed.”

Open house

To celebrate Point Hope’s 150th, the shipyard is holding an open house celebration on June 18 from 11 a.m. until 4 p.m. at 345 Harbour Rd.

The event will include tours, exhibits from the Maritime Museum of B.C. and model shipbuilding, a job fair, live music and artists.

Victoria Harbour Ferries will be offering free trips to the shipyard to mark the anniversary.

>>> To comment on this article, write a letter to the editor: [email protected]