OTTAWA ŌĆö Justin Trudeau likes to warm up for an uphill election contest by literally climbing uphill. In the 2015 campaign, as he attempted to vault his third-place party into the lead, the Liberal leader took time out to tackle the Grouse Grind, the gruelling 2.9-kilometre trail up the steep face of a mountain overlooking 91įŁ┤┤.

He managed to scale ŌĆ£Mother NatureŌĆÖs StairMasterŌĆØ in 54 minutes and 55 seconds, well under the average 90 minutes. He left some sweating reporters, photographers and assorted followers in his dust ŌĆö and did the same a few weeks later to his older rivals Stephen Harper and Tom Mulcair on election day.

Late last month, on the cusp of a campaign for a second term, Trudeau managed to shave two minutes off his 2015 time, even with pauses for selfies with other hikers.

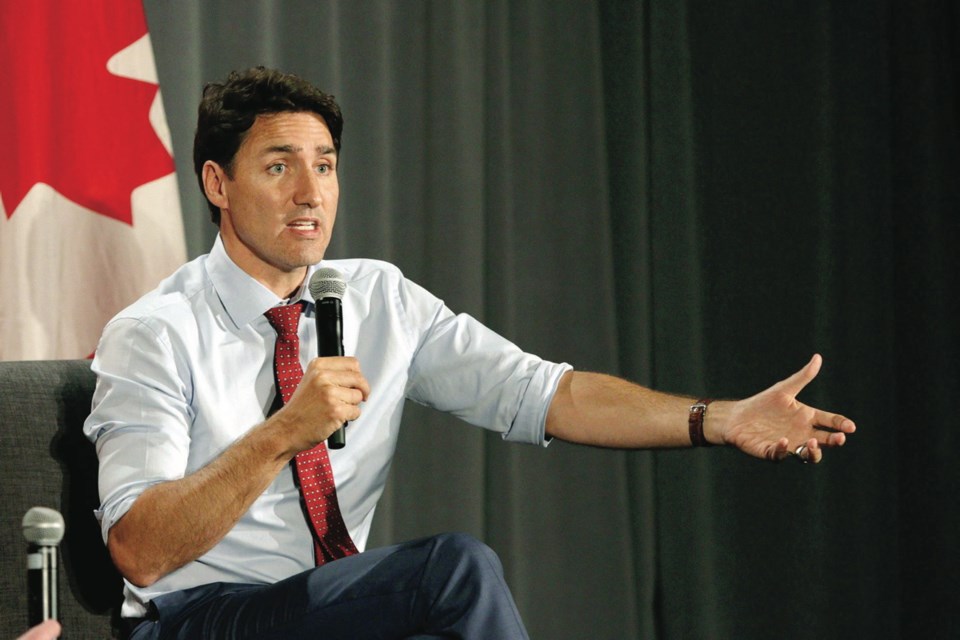

ŌĆ£I was [thinking], OK, IŌĆÖm four years older, IŌĆÖm four years into this job, letŌĆÖs make sure IŌĆÖm still in shapeŌĆÖ and I managed to cut two minutes off my time, which means I may be a little older but IŌĆÖm not that much older,ŌĆØ he said with a grin a few days later, during an interview in a Hamilton coffee shop after participating in protest-interrupted Labour Day festivities.

This time, at 47, heŌĆÖs the oldest leader of any of the three traditional parties. And heŌĆÖs hauling political baggage with him.

ŌĆ£When youŌĆÖre running for the first time, people get to project all their hopes and dreams onto an individual and I was honoured to carry those hopes and dreams,ŌĆØ Trudeau says now.

But inevitably, Trudeau has not lived up to those expectations, some of them encouraged by his own soaring rhetoric and ambitious platform promises in 2015.

HeŌĆÖs disappointed some by abandoning his promise to change CanadaŌĆÖs first-past-the-post electoral system, others by reneging on a promise to run modest deficits for a couple of years before balancing the federal books. Environmentalists complain heŌĆÖs not done enough to combat climate change, while for others heŌĆÖs done too much, hobbling AlbertaŌĆÖs oil industry and slapping a carbon tax on consumers.

HeŌĆÖs faced accusations that his agenda of reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples is more talk than action. HeŌĆÖs been ridiculed for playing dress-up during an ill-fated trip to India last year. HeŌĆÖs been found to have violated the ethics code for parliamentarians, twice. Two prominent cabinet ministers resigned over the SNC-Lavalin affair.

As a result, TrudeauŌĆÖs Liberals are entering this campaign roughly tied in national popular support with Andrew ScheerŌĆÖs Conservatives ŌĆö slightly ahead or slightly behind, depending on the poll ŌĆö with neither party positioned to win a majority.

Trudeau is hoping 91įŁ┤┤s will conclude that heŌĆÖs at least taking the country in the right direction.

ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm not going to make any apologies for being very ambitious about what we wanted to do [in 2015],ŌĆØ he says, insisting that his government has delivered ŌĆ£massive thingsŌĆØ on the environment, support for the middle class, Indigenous reconciliation and international trade.

ŌĆ£Yes, there is more to do. There is always, always going to be more to do. I┬Āthink weŌĆÖve demonstrated really good capacity to move in the right direction.ŌĆØ

However short of expectations Trudeau has fallen, there is still something of a celebrity aura about him. At HamiltonŌĆÖs Labour Day parade, a small group of vocal protesters grabbed the spotlight but, for the most part, paradegoers seemed thrilled to see the prime minister, flocking to him for a chance to shake his hand and pose for selfies.

ŌĆ£This is my first time seeing Trudeau and IŌĆÖm kind of dazed. Whoa,ŌĆØ gushed one young woman to a friend.

ŌĆ£I donŌĆÖt vote on it but he does have far nicer hair than I do,ŌĆØ joked a more dispassionate, balding man. ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm envious.ŌĆØ

Trudeau insists heŌĆÖs committed to the sunny way of doing politics: appealing to 91įŁ┤┤sŌĆÖ better angels, eschewing the politics of fear and division that he accuses the Conservatives of practising.

That said, he defines the sunny approach to politics narrowly: it doesnŌĆÖt mean he wonŌĆÖt have ŌĆ£sharp disagreementsŌĆØ with his opponents. HeŌĆÖll just avoid what he considers personal attacks.

Reminding voters that Scheer has long opposed abortion, voted in the past against same-sex marriage and has never marched in a Pride parade does not, in TrudeauŌĆÖs mind, constitute a personal attack ŌĆö notwithstanding ScheerŌĆÖs pledge that a Conservative government would not reopen either issue.

ŌĆ£YouŌĆÖre right, we shouldnŌĆÖt be overly critical about what someoneŌĆÖs faith or personal beliefs are,ŌĆØ says Trudeau.

ŌĆ£But if they have implications for how he would govern, I think itŌĆÖs absolutely right for 91įŁ┤┤s to be asking questions and for us to be highlighting that, in my mind anyway, a leader is someone who stands up for people, he doesnŌĆÖt just reluctantly obey the law.ŌĆØ

Like Scheer, Trudeau is a practising Catholic. ŌĆ£My faith informs the person I am in my own values, in my approach and my desire for service,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£But I disagree with the Catholic ChurchŌĆÖs teachings on womenŌĆÖs rights and on the rights of the LGBTQ2 community.ŌĆØ

He became the first prime minister to join Pride parades, celebrating people who have faced treatment that he says ŌĆ£is almost the embodiment of what discrimination is.ŌĆØ And he sees that as a vitally important part of the job.

ŌĆ£This is a community that was told explicitly or in subtle ways that they should be ashamed of who they were, of who they loved, that they should hide in the closet. ... So that is where, when a prime minister walks in Pride, youŌĆÖre saying: ŌĆśNo, this is something to celebrate, this is who you are, donŌĆÖt let anyone tell you you should be ashamed.ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ

ItŌĆÖs a message, he adds, thatŌĆÖs important not just for the LGBTQ2 community but for all minority communities ŌĆ£whoŌĆÖve been marginalized, whoŌĆÖve been ignored, overlooked or pushed aside.ŌĆØ

But asked about his biggest regret from the past four years, he chooses his inability to prevent the global forces of polarization from seeping into Canada. He muses that ŌĆ£perhaps some of the things we do challenging people on LGBT rights or diversity in immigration or feminism has created backlashes that I wonder if I could have been just as strong in standing up for what is right and what I deeply believe in without making it a source of polarization or making it a place where other people could choose to polarize.ŌĆØ

He cites ŌĆ£the mild resurgence of a separatist movement in AlbertaŌĆØ as another example of polarization that worries him. He never expected conservative Albertans to love him, he says, but he did hope heŌĆÖd at least get credit for trying to help, including by spending $4.5 billion to push a major pipeline project forward.

As for his proudest achievement, Trudeau chooses the single, means-tested, tax-free Canada Child Benefit ŌĆö a measure he boasts has lifted 300,000 children out of poverty and has made a tangible difference to families struggling to make ends meet.

Like Trudeau himself, his own children ŌĆö Xavier, 11, Ella-Grace 10, and Hadrien, 5 ŌĆö have never faced deprivation. But they do have different challenges, among them coping with insulting things said about their dad. Trudeau says he and wife Sophie Gr├®goire Trudeau are trying to raise them the way his late father, Pierre Trudeau, raised him: ŌĆ£Nothing [critics] say actually gets to define who I am and nothing anyone says about you gets to define who you are and you just have to build a strong core yourself.ŌĆØ

TheyŌĆÖre also trying to impress on the children that being born into privilege carries a responsibility ŌĆ£to do right by the chances and opportunities given to you and make sense of your role in the universe by making a positive difference in the world around you.ŌĆØ