AT THE GALLERY

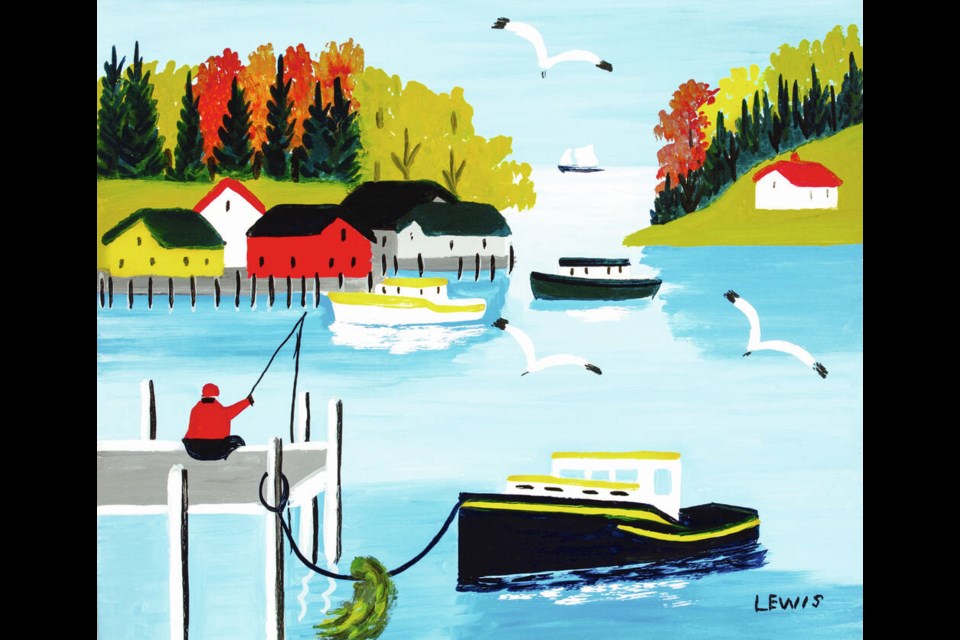

What: Maud Lewis

Where: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 1040 Moss St.

When: June 18-Oct. 16

Admission: $13 (adults) and $11 (seniors and students); children five and under free

Note: Public open house from 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Saturday is free and open to the public

Maud Lewis was not a worldly traveller, nor did she aspire to be. But work by the Nova Scotia painter has found an international audience in recent years, with her charming folk art creations now among the most recognizable in Canada.

That’s one of many fascinating legacies Lewis left behind, and a recurring theme of Maud Lewis, a new exhibit at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria which opens Saturday.

“It’s very accessible to people, and it’s very optimistic,” gallery director Nancy Noble said of Lewis’s work, which will be on display at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria through October. “She was an ordinary person but an extraordinary artist.”

More than 130 pieces by Lewis, including some rarities, are included in the Victoria exhibit, which is curated by Ontario’s McMichael 91原创 Art Collection. Maud Lewis was culled from a variety of sources, including several private collections and the deep trove housed at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, where Noble was CEO for six years. Victoria is the exhibit’s only B.C. stop on a cross-Canada tour that has captured Canada’s imagination.

Having just arrived from Halifax — Noble’s first day at the Victoria gallery was June 6 — she expects there will be a strong local reaction to the work of the acclaimed artist from Atlantic Canada.

“Halifax and Victoria — not that she lived in Halifax — are very similar-sized communities and they are both coastal, and they are both defined by the ocean in some sense.

“People are really going to find this interesting, her depiction of the East Coast, which is some ways will be familiar to people on the West Coast.”

Lewis she died of pneumonia at 67 in 1970, in Digby, N.S., where she lived for more than three decades. Lewis did not travel more than an hour away from home at any point during her life, choosing instead the comfort of the impossibly tiny one-bedroom house (which measured 3.75 metres by four metres) she shared with her husband, Everett Lewis.

The couple were seen as eccentrics by many among the rural community. Everett was an irascible and miserly fish peddler and farm labourer who buried his money in glass jars around their property; Maud was a diminutive and shy woman born with physical difficulties that caused her to drop out of school at 14. Lewis was well-known, however, for selling postcards to tourists for 25 cents from the front stoop of the couple’s roadside home, which had no plumbing and had oil lamps instead of electricity.

“For the kind of life that Maud Lewis lived, her work is happy,” Noble said.

“It’s colourful. She has kind of a naive sense of place, but she painted what she knew, and what was around her. I think people can relate to that.”

Some historians believed Lewis had symptoms akin to those associated with polio, but she was never given a proper diagnosis. This led to crippling arthritis as an adult, which greatly affected the manner in which she painted. The primitive nature of her creations, which often involved animals such as cats, deer and oxen, is what made her work so appealing to some.

Some of her important work — including her lovingly painted house — is on permanent display at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, and is treated with the highest regard.

Lewis has risen to rock star-like levels in recent years, thanks in part to the 2016 film Maudie, starring Sally Hawkins as Maude (sometimes referred to as Maudie) and Ethan Hawke as Everett. The well-reviewed film grossed nearly $10 million US worldwide, and renewed appreciation of Lewis’s work. Her paintings even appeared on Canada Post’s line of holiday stamps in 2020.

“After the movie came out, there was a much greater awareness,” Noble said. “People want to collect her work now, because they are more aware of what she did.”

Buzz about the film swept up Noble along the way. Her first day as CEO at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia put her in Toronto for the world premiere of Maudie, which screened at that year’s Toronto International Film Festival. And when a 2017 news story, about a Lewis original discovered amidst donations at an Ontario thrift store, drew international headlines, it was Noble who was sent to retrieve it.

“I happened to be in Toronto at a conference [when it was discovered], so I rented a car, drove to Kitchener-Waterloo, picked up the painting, and flew it back to Halifax,” she said with a laugh. The painting, Portrait of Eddie Barnes and Ed Murphy, Lobster Fishermen, was appraised at $16,000 but eventually sold at auction for $45,000.

“I was terrified. It hadn’t sold [at that time], so nobody knew what its value was going to be, but there’s me on an airplane, clutching this thing to my chest,” Noble said. “I wouldn’t let it go.”

At the time, paintings by Lewis generally sold for less than a quarter of that sale price, which speaks to the ever-growing appeal of her work and interest in her story.

Noble said she sees a parallel between the works of Lewis, a beloved figure in Nova Scotia, and Emily Carr — two larger-than-life personalities whose evocative art brought recognition to their respective home provinces.

“They are very different artists, obviously, but it’s not so much about the artist,” Noble said. “It’s about the person and their connection to community, in the way they worked and where they lived and the people they knew.”