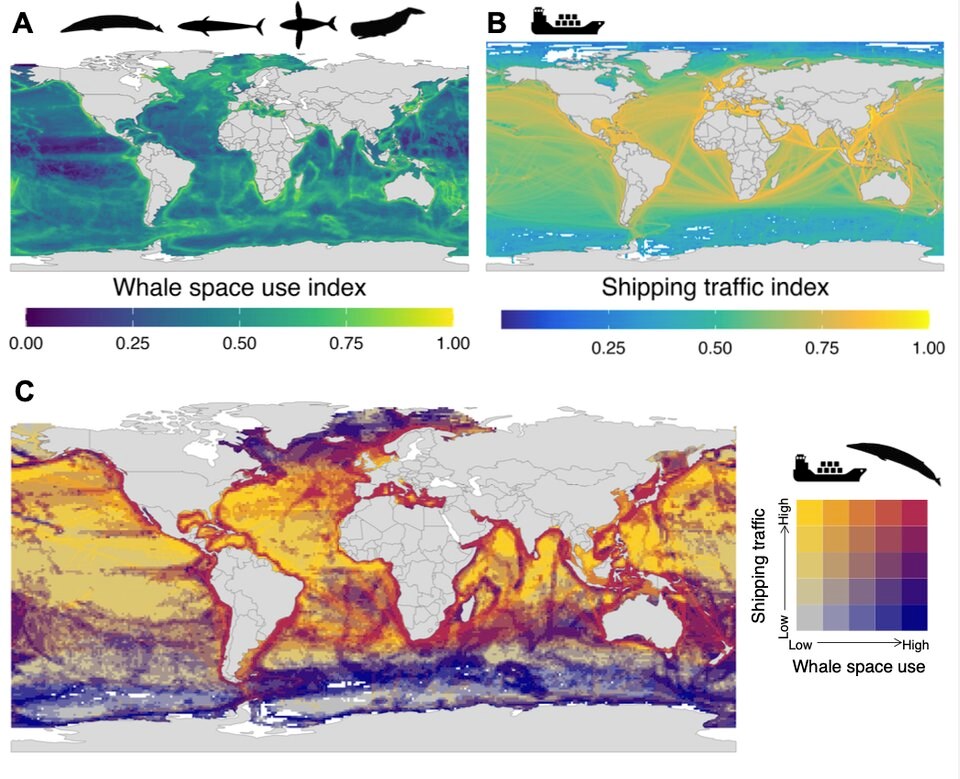

Global shipping routes overlap with 92 per cent of the of migration routes of four globe-ranging whale species, a new study has found.

The research, published in the journal Thursday, marks the first time anyone has quantified worldwide risk of whale-ship collisions for blue, fin, humpback and sperm whales.

Chloe Robinson, an ecologist and director of the Ocean Wise’s Whales Initiative, said the research identified several previously unknown high-risk zones including one large one off the southwest coast of 91ԭ�� Island.

“This helps us to pinpoint where whales are most vulnerable,” said Robinson, who co-authored the study. “There's never really been anything this comprehensive before.”

Global databases show high risk of deadly 'odds game'

The research team spanned five continents and drew on 435,000 unique whale sightings — from government surveys, sightings by members of the public, animal-borne GPS tags, and even whaling records going back to 1960.

They then compared that cetacean data with the movement of 176,000 cargo ships from 2017 to 2022. The vessels were tracked through their automatic identification system and cross-referenced with whale ranges to identify where they would likely meet.

“We’re talking about five billion vessel positions,” said Robinson. “It’s a bit of the odds game. The more whales and vessels you're going to have overlapping, the more likely you are that one of those encounters is going to end in a ship strike.”

Every year, the total distance large container vessels travelled through whale ranges was found to be greater than 4,600 times the distance between the Earth and the moon, said lead author Anna Nisi, a postdoctoral researcher in the University of Washington’s Center for Ecosystem Sentinels.

Along with entanglement in fishing gear, ship strikes represent a leading threat to large migrating whales. But Nisi said studying ship collisions can be incredibly difficult. Most of the time, she said, a vessel will strike a whale and it will sink on impact without anybody noticing.

“Sometimes they roll into port with the whale draped over the front of the ship, and that is how they realize that they've hit something,” Nisi said.

Ship-strike hot spots pinpointed around the world

In the Americas, the highest risk areas for whale-ship collisions were found along North America’s 91ԭ�� coast, as well as off Panama, Brazil, Chile, Peru and Ecuador. Elsewhere in the world, hot spots for collisions were identified in southern Africa; the Canary and Azores Islands; the Arabian Sea and Sri Lanka; and in East Asia, off the coast of China, Japan and South Korea.

Past studies have found some of those areas already had a high risk for whale-ship collisions. Robinson said scientists had a pretty good understanding of where vessel and whale routes overlap in 91ԭ�� nearshore waters. But move further offshore, and the risks of whale-vessel collisions become a lot murkier — until now.

The study found that off the southwest point of 91ԭ�� Island, a high concentration of vessels are crossing through the same waters humpback and fin whales use to migrate, feed and relax.

The hot spot for whale-ship collisions lies just outside an existing management zone set aside for southern resident killer whales at . The area — which includes seasonal speed limits and fishing closures — extends about 40 kilometres along the west coast of 91ԭ�� Island between Port Renfrew and Bamfield.

A little further west, the study found what Robinson described as a pit stop on a whale highway, where humpbacks and fins feed and rest before entering the Salish Sea or continuing on their migratory path north and south.

“It is somewhere where if there are strikes, they're very unreported,” she said.

Ship strikes increasing in B.C. waters

The study comes amid a rebound in humpback whale populations and an increase in maritime traffic. The combination has amplified collision risks, according to Robinson.

Between 2022 and 2024, Ocean Wise tracked at least 15 whale strikes in B.C. waters. And while another recent strike is still being investigated, Robinson says the actual total is much higher as most collisions go unreported or unnoticed.

“This is something that we see more and more every year,” Robinson said. “Across the coast of B.C., there were at least 10 humpbacks struck in 10 different instances — just last summer. And this is just what we know.”

Humpback whales are born into a life of migration — every year passing between northern and southern feeding and breeding grounds. Instead of avoiding ships, the whales tend to sleep at the surface during their migration, a position that makes them incredibly difficult to see and puts them at a high risk of being struck.

“As more and more whales return, we're seeing more and more strikes,” said the ecologist. “Vessels have increased 300 per cent in the last 30-odd years. So it's a real concern for these species.”

The big question, she said, is whether all the deaths by ship will inhibit the whale’s future growth.

Highest risk of strikes occurs in territorial waters

Across the world's oceans, the study found more than 95 per cent of the hot spots for whale-ship collisions are located near the coast, where countries have the capacity to protect marine life within their exclusive economic zones.

Yet only seven per cent of the areas at highest risk of collision were found to have any measures in place to protect whales.

Alongside the grim numbers, the researchers also offered data that suggests protecting whales might not come with a prohibitive cost to shipping.

Installing management regimes in only another 2.6 per cent of the ocean’s surface would protect whales in all of the highest risk locations, found the study.

“It's a small percentage, but of course, a very large area,” said Nisi. “This means that there's just a lot of need and a lot of opportunity to expand these protection measures for whales.”

Long-term co-existence requires collaboration with industry, says ecologist

Robinson said about two decades ago, global shipping companies and port authorities across B.C. and Washington tended to use whale conservation measures as a way to greenwash their operations. But efforts to slow and re-route ships passing through whale ranges have improved in recent years.

In Sri Lankan waters, the Swiss-Italian-owned Mediterranean Shipping Company has voluntarily re-routed their vessels around an important whale range, said Robinson.

“Striking whales is bad, not only for their image, but for the environment. And they're supportive of these measures because they're looking for that long-term coexistence,” she said.

Closer to home, a system of hydrophones, infrared devices and human reporting now informs nearshore whale alert systems from Washington to B.C. and Alaska.

What needs to come next, said Robinson, is to expand that system to previously unknown hot spots further from the coast, such as the area identified west of Swiftsure Bank.

That could mean as little as extending the Swiftsure Bank management area by a few kilometres to help humpback and fin whales — two species who can't echo-locate objects like their toothed killer whale cousins.

“They're not evolved to avoid these vessels,” Robinson said. “This is really problematic.”